The Outsiders

Written by Francis Ford Coppola & S. E. Hinton

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

It was partly made out of Coppola’s dire need to pay off accumulated debts and an homage to the rebel films of the director’s youth. Based on the first young adult novel, The Outsiders follows teenager Ponyboy (C. Thomas Howell) as he grows up in a small Oklahoma town where the poor kids are constantly being targeted by the wealthy ones. Pony’s best friend Johnny (Ralph Macchio) accidentally kills one of these preppies out of self-defense, which sends the two boys scrambling into hiding. Through this trial, they are forced to confront the fragility of life and the beauty that each new day brings. Coppola created an emotionally moving and volatile film that captures the chaos of being a young adult. There are some stunningly beautiful images here where the director embraces the intentional artificiality of film in order to strengthen the visuals. The film also introduced us to many white boys who would dominate movies over the next decade, including a pre-dental work, Tom Cruise.

The Big Chill

Written and directed by Lawrence Kasdan

This film seems to have been viewed as a pity party for Baby Boomers, but I got a very different read of the picture. A group of college friends, now in the middle of their 30s, gather together to mourn the suicide of one of their own. Over the following weekend, they reflect on how they have changed since those youthful days and how meaningless many of their lives have become. I never felt that Kasdan was giving blanket sympathy to them, nor was he leveling a harrowing judgment. Instead, he allows us to see these people for all their flaws beneath the seemingly beautiful surface. The ending doesn’t provide us with happy closure, everyone figuring out their problems. The problems remain, and they walk away with a better understanding of themselves, but likely not enough to change anything. I find The Big Chill a perfect film for spotlighting the bleak path ahead for this generation that had burned out so hard after a chance at better days. It was clear that Reagan-era America didn’t want to self-reflect in the way Kasdan emphasizes here.

The 4th Man

Written by Gerard Soeteman

Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Paul Verhoeven is known for making some batshit crazy American films, but he was already doing that in his early Dutch work. The 4th Man is an homage to Hitchcock and its own wild experience. Gerard is a writer on a trip to give a lecture. On the train, he encounters a man he is immediately attracted to, but his flirtations go nowhere. At his destination, Gerard meets Christine, a local who invites him back to her place. After they sleep together, Gerard discovers the man from the train is her lover, Herman. Gerard decides to get entangled in this relationship to steal Herman away, only to suddenly become convinced that Christine is a black widow, murdering her partner. Verhoeven fills this movie with incredible transitions and dreamy imagery that keep the viewer skeptical of what we see from Gerard’s perspective. This one is an underrated gem that deserves to be rediscovered.

San Soleil

Written & Directed by Chris Marker

Chris Marker continues his experimental filmmaking career with this feature-length documentary using stock footage and Japanese media. Rather than exploring a topic through interviews, the film takes the form of a poetic essay, fictional letters written about a journey across the world. We explore ideas of time and space through dialogue and images and how distant geographical points and cultures can be connected through chance. Marker is interested in how people move through spaces that can appear different on the surface, only to discover strong connections between them the deeper they dig. The director references Hitchcock’s Vertigo, another film about how time & space can get tangled up in our heads. This one is a film that a person will either love or hate, and it doesn’t try to make itself something easy to digest or even comprehend on a first viewing.

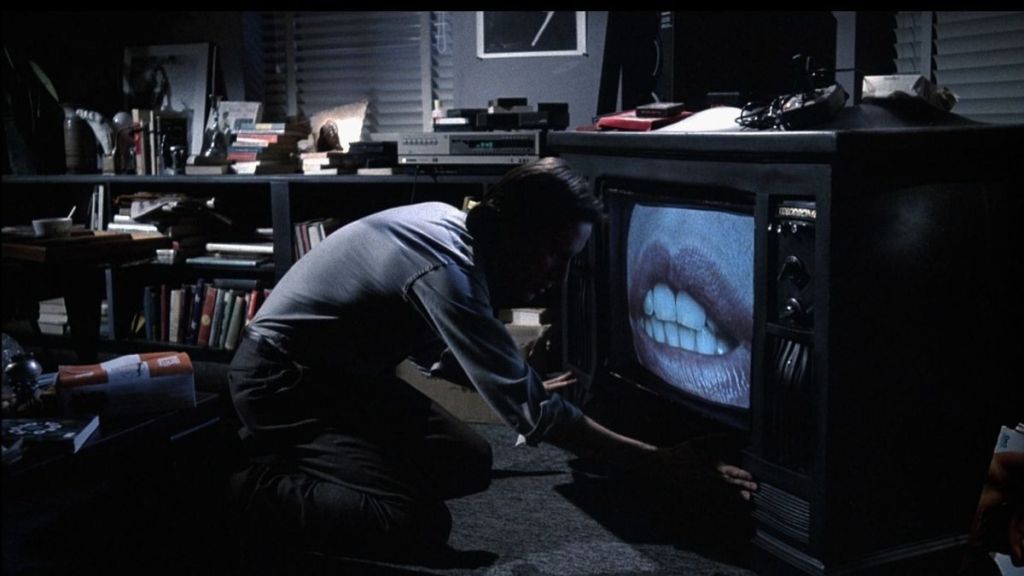

Videodrome

Written & Directed by David Cronenberg

The same year, Canadian director David Cronenberg directed The Dead Zone; he also released this (better) body horror film about how mass media reshaped the human experience. Max Renn (James Woods) is the president of a Toronto TV station and discovers strange foreign programming being picked up on the unlicensed satellite dish. They depict what amounts to snuff films, and Renn becomes captivated by them, as well as his new lover, Nicki Brand (Deborah Harry), a sadomasochistic radio host. After Nicki goes missing, Renn seeks the help of Brian O’Blivion, an enigmatic media theorist who leads down a twisted rabbit hole. Videodrome is a nasty piece of work, but that’s precisely what it needs to be. Cronenberg takes us beyond the simplistic morality of the old world and shows us the ways exposure to images & ideas acts as a virus, infecting and changing humanity. Even today, Videodrome feels like a forbidden film, a movie that says things it doesn’t seem we should be allowed to hear.

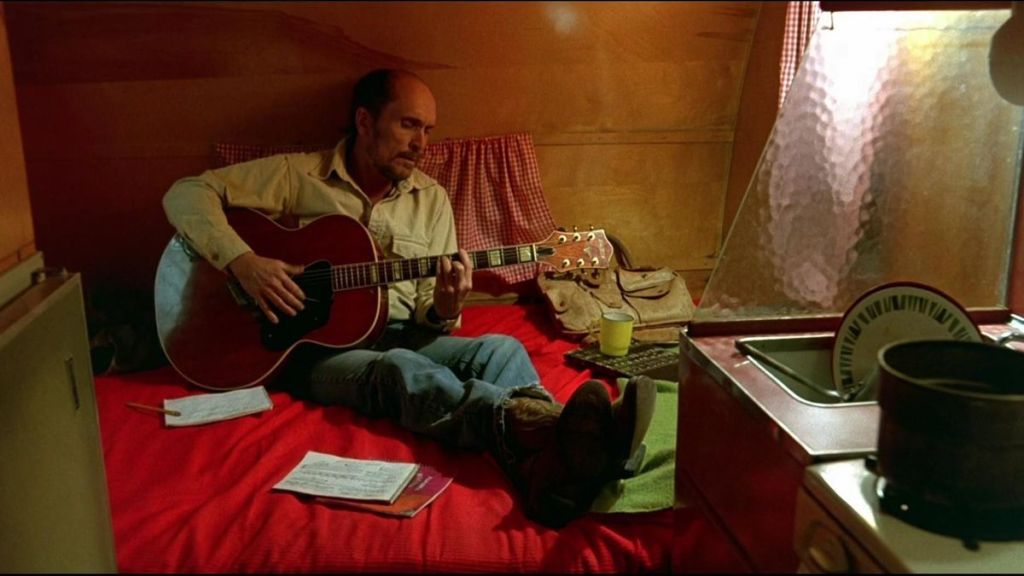

Tender Mercies

Written by Horton Foote

Directed by Bruce Beresford

Mac Sledge (Robert Duvall) is an alcoholic country music singer who finds he’s far from home at a motel & gas station on a rural Texas roadside. He offers to help around the place, and this is looked upon favorably by the owner & single mother/widow, Rosa Lee (Tess Harper). Her husband died in the Vietnam War, and her son, Sonny, has been left without a father. Mac’s low profile quickly evaporates, and he is pulled back to what he left behind: his successful ex Dixie (Betty Buckley) and their 18-year-old daughter. The film is a beautiful & painfully human exploration of shame & redemption, Mac coming to terms with how he abused Dixie during drunken rampages. There are happy moments and painfully tragic ones, too, but the film never attempts to make sense of this. Life is comprised of a small part of what we make of it and a large part of random things that happen to us. Mac struggles with understanding why moments of happiness always seem dashed away by tragedy. He doesn’t find the answer but finds a way to keep going. It’s the story of life we all experience.

Pauline at the Beach

Written & directed by Eric Rohmer

Teenage Pauline and her adult cousin Marion spend part of their summer on the north-western French coast. Marion runs into her ex-lover, Pierre, on the beach only to be interrupted by Henri, an acquaintance of Pierre’s. Henri pushes for a dinner for all four of them and quickly makes his intentions for Marion known, using his wealth to upstage the working-class Pierre. Marion wants a whirlwind love affair, something overflowing with passion, while Pierre desires a more authentic experience. Henri takes full advantage of this. Pauline is the outside observer, learning about the complexity & dysfunction of adult relationships, and realizes she has come to an age where she wants to know what actual love feels like between two people. The problem is that none of the adults she’s surrounded by know what that is either. This was my first Eric Rohmer film, and I’m intrigued to watch more of his work soon. It’s very European in its stylistics and deceptively engrossing.

Meantime

Written and directed by Mike Leigh

Mike Leigh has been a strong voice for the British working class throughout his career. This entry is about the Pollock family, people ravaged by the economic policies of Thatcher-era England. Colin (Tim Roth) has learning disabilities and has become painfully shy. His older brother Mark (Phil Daniels) can’t help but keep fruitlessly raging at the society around him. They wander through a world where skinheads have popped up due to economic struggles. They also have a family member who has positioned themselves as middle-class and trying to hide away from their lower-class roots. Leigh never attempts to tell us how all these problems are solved; he simply lets the character come to life on the screen. Like most of his films, some of these characters will grate on you, but that’s part of the point: people who make themselves larger than life to deal with how little power they have daily.

L’Argent

Written & Directed by Robert Bresson

L’Argent was French filmmaker Robert Bresson’s final picture, and he went out with an incredible one. Based on the Leo Tolstoy novella The Forged Coupon, the story follows not a character but a counterfeit 500 franc note. A young man needs money, but his father won’t give it to him, so he pawns his watch to a friend who gives him the fake bill. The boy goes to a photography store where he purchases something to mostly get back change and burden the store with phony money. Eventually, it ends up in the hands of Yvonn, and when he tries to pay the tab at a restaurant, he is arrested. Bresson includes Marxist ideas about workers, wages, and the justice system while not losing sight of the poetic aspects of human existence. Events snowball wildly out of control, concluding a scene that leaves us in stunned silence. How did we get from a counterfeit note to the human devastation we see at the end. Was justice served in any way?

A Nos Amours

Written by Arlette Langmann & Maurice Pialat

Directed by Maurice Pialet

I was stunned by this incredibly complex & beautiful French drama. Suzanne (Sandrine Bonnaire) is a fifteen-year-old who starts exploring her sexuality with young men in her friend group. While she begins to understand the difference between loving someone and desiring sex with them, her family falls apart. Suzanne’s father suddenly abandons them for his mistress, which sends everyone into a chaotic freefall. What affected me so much about this film is the refusal to soften the blow of how much this young woman’s declaration of herself is reviled by her family. We are shown something rarely put on screen: a young woman presented as an autonomous, free-thinking human being. Suzanne quickly realizes how her fate is forcibly tied to her relationship with men, be it her father, her brother, or one of her lovers. For so much of society, she is defined purely by these relationships. Told in a neorealist style reminiscent of John Cassavettes, A Nos Amours presents its main character with such sensitivity and nuance it puts other similar films to complete shame.

One thought on “My Favorite Films of 1983”