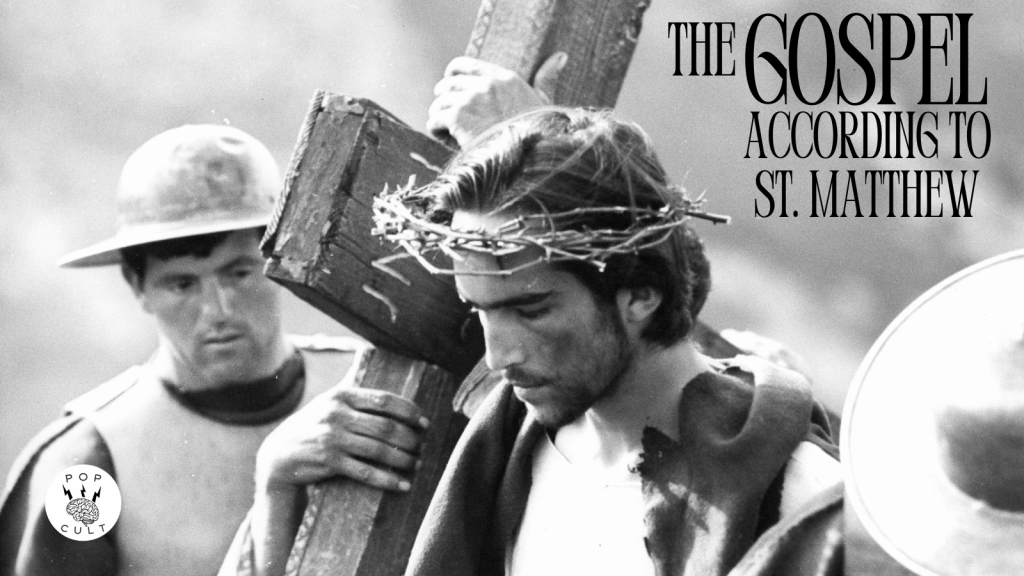

The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964)

Written and directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini

It may seem like an incredibly odd match. A queer, atheist, communist Italian man making a film about the life of Christ. Even more bizarre, it was In an effort to find relevance in the landscape of the post-war world, Pope John XXIII had asked for an audience with contemporary non-Catholic artists. Pasolini had been raised in the Church and accepted the invitation, knowing so much of his identity clashed with the institution. The meeting occurred in Assisi, and the subsequent traffic jam caused by the Pope’s presence in town left the filmmaker stuck in his hotel longer than he had expected. Pasolini claims he paged through a Bible in the hotel room, reading through each of the Gospels and settling on Matthew as the perfect one for the film he had in mind. His opinion was that the three other Gospels embellished or lacked a clear perspective on Christ; Matthew’s gospel was the most human.

The film follows the life of Christ, starting with Mary’s part in the story. With barely any dialogue, we experience Joseph’s reaction to Mary’s story of carrying the child of God. Pasolini uses the neo-realism style and his own heavily symbolic aesthetic to create a story of Jesus, unlike anything you’ve seen before. Pasolini unfolds familiar events from the gospels but presents them very groundedly. Miracles happen, but the filmmaker is less interested in those than he is in the idea of Jesus as a peasant revolutionary. Pasolini isn’t afraid to play with anachronistic costuming to have a look that provides an interesting contrast to social realism. This is a trend that will continue throughout Pasolini’s subsequent historical adaptations.

What Pasolini accomplishes with this film is something I have seen summed up in several reviews: transcendent. The best example of this for me is the sequence where the Three Magi come to visit Mary. There’s no dialogue here save through Pasolini’s soundtrack choice – “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” covered by Odetta. Juxtaposing this contemporary music track with a familiar Biblical event creates a new tone. The humanity of these mythic figures is revealed. Mary, actually played by a fourteen-year-old girl here, feels like someone trying to make sense of many confusing things coming at her all at once.

Pasolini had been accused of blasphemy the year before this film’s release for his short film La Ricotta (which I have not seen), which depicted Jesus in a way that offended Catholics. It’s amazing that shortly after, he made a film about Jesus’s life that was officially endorsed by the Church. The love affair wouldn’t last because Pasolini wasn’t interested in courting favor from these institutions. He wouldn’t shy from the opportunity to prove his intentions weren’t insulting but seeking to bring these lofty myths down to a human level. He reminded the bourgeoisie that these important figures did not come from the wealthy class but always from the underclass.

To pull this off, he employs non-professional actors who perform without pretensions, adding to the realism. His locations are not expensive sound stages but on location in rough, deprived places. It was an extremely effective way of presenting this story and suddenly compressed two thousand years of distance between the audience and the narrative. We can see ourselves in these people. The lyrics of “Motherless Child” sound like they could be narrating the unspoken dialogue of baby Jesus or maybe even Mary, still a child herself and adrift in a confusing world.

Jesus is not a meek figure but one who feels tremendous anger towards the wealthy class and those who help to uphold it. His Sermon on the Mount includes a fiery rendition of this familiar verse: “And again I say unto you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.” The Biblical depiction of Christ is broader and never provides much tone for how Jesus says these things, but Pasolini sees a person furious at a world that has allowed so many to suffer so a select few can live in luxury. I’m a nonbeliever, and even I was emotionally moved by this, something that hasn’t been accomplished by any other film depiction, including Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ.

This also signals a dramatic shift in Pasolini’s narratives. For the remainder of his career, most of his work will adapt classic Western texts, and he allows himself artistic license for creative production design. I can’t help but think Ken Russell was at least in part inspired by this for his tremendous historical horror film The Devils. As we’ll see with the upcoming films, Pasolini works hard to present the humanity of figures like Oedipus and Medea, just as he does here with Jesus. He is right in understanding that we cannot find love in our hearts for people raised so high on a pedestal that we can’t see them anymore.

2 thoughts on “Movie Review – The Gospel According to St. Matthew”