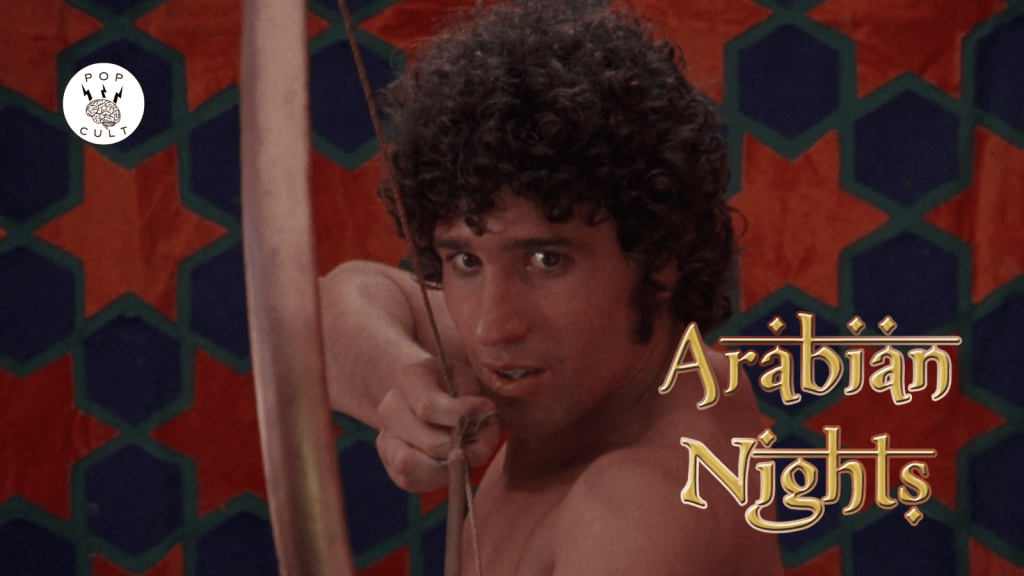

Arabian Nights (1974)

Written by Dacia Maraini and Pier Paolo Pasolini

Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pier Paolo Pasolini would be dead a year after Arabian Nights’ release. It was the final film in his Trilogy of Life, preceded by The Decameron and The Canterbury Tales. Of all his work, it was the first to fully embrace queerness. Pasolini was a homosexual who existed in a strange tension with the Catholicism in which he had been raised. His work often looked to the past to comment on or understand some aspect of the future. Instead of focusing on the misery of the peasant class, Pasolini sought to display the joy experienced by those people the wealthier parts of society often dismissed. These classic stories that had shaped so many people’s imaginations were the perfect soil from which to grow that seed.

What’s immediately different with Arabian Nights versus the first two films in this trilogy is the absence of an authorial figure. In The Decameron, Pasolini plays a muralist whose painting reflects the stories told in the movie. For The Canterbury Tales, the director plays Chaucer and even recreates a well-known illustration of the writer at work. There is no authorial presence in Arabian Nights which is accurate because we do not know who wrote the original text, simply that it exists. This is Pasolini’s furthest journey back into the past as he searches for a history that can inform the world as he wishes it to be, a place where someone like him can thrive and live without hiding their sexuality.

Pasolini drops the framing device of the slave Scheherazade, delaying her execution by telling the bloodthirsty king stories that take up night after night. Instead, he takes the stories that stood out to him most as a child and chops them up into scenes, allowing the film to stretch the stories out over its runtime. What ends up framing the film is the tale of Zumurrud and Nur ed-Din, whose first scene opens the film and whose conclusion is the final sequence we see.

Zumurrud is an enslaved girl being offered up at auction. Man after man offers great sums of money to buy her, but her present owner has said she can have the final say. Zumurrud rejects these old, weathered men. She settles on Nur-ed-Din, a young man without any money. Throughout the film, the couple deals with societal forces that wish to tear them apart. For a time, they are separated, and during these separations, they step into the stories of other characters who get a bit of the spotlight for a short time.

Pasolini presents an “Arabia” that is not exoticized as other incarnations often do. He shoots on location in Yemen, Iran, and Nepal, where most production design involves removing objects that identified the time as the mid-late 20th century. The cities and buildings he films in are restored as closely as he can get to what they would have originally looked like, so we feel like we are in a world without the all-consuming shadow of mass consumption and capitalism looming over our shoulders. Yet this is also a world where the fluidity of sexuality is fully embraced, and for the first time, Pasolini is presenting overtly homosexual characters on screen.

Part of Zurmurrd’s story involves her posing as a male ruler behind an ornate mask. The people in her kingdom remark about their king’s seeming love for men as Zurmurrd searches for her lost partner. Sexuality, in the way these characters discuss it, exists in the realm of taste rather than an all-consuming identity. I think Pasolini’s view of sexuality was not that some people are born straight or gay but that everyone has a fluid sexuality. In the view of the king’s subjects, sometimes he prefers women and others for men, and none of them are bothered by this idea.

Some of Pasolini’s real life is coming through in one of these stories. Ninetto Davoli was an actor whom Pasolini found to be his muse and with whom he developed romantic feelings. During the production of The Canterbury Tales, Davoli had told Pasolini he was engaged to a woman and that any sexual or romantic relationship they had would be ending. It reportedly hit Pasolini very hard. In Arabian Nights, Davoli plays Aziz, a man who abandons his wife-to-be to run away with another woman on the wedding day. The spurned woman gives Aziz advice on how to win the heart of this other woman and then dies from the grief of losing her man. Davoli had lived with Pasolini for ten years when the split occurred, and this sequence in the film is dripping with his pain.

The core theme of Arabian Nights is the powerful embrace of love & sexuality. This has the most nudity and sex of all of Pasolini’s films and underlines what he saw as the purpose of life. In the artist’s opinion, the connections we make with each other define life. And those connections that exist outside the realm of formal language are the most powerful. The physical connection of sex between two lovers is the greatest of them all, the inability to contain those feelings within, that these emotions must manifest in the material realm to provide those who hold them with relief. Sexuality, as long as it is consensual, cannot be sinful in Pasolini’s view. It is the purest form of love that exists.

Pasolini’s next project was the start of his Trilogy of Death, the shadow of this series. Salo, or 120 Days of Sodom, would kick that off. But then the filmmaker was murdered, his battered & burnt body found on a beach after responding to ransom for stolen reels of his film. He was only 53. It’s so angering because there was so much more Pasolini could have made and wanted to make. His career was nowhere close to being over, yet cruel & vicious hate stole him from the world. His killers were far-right terrorists, the same type of people who are coming to power throughout the West right now. We must look to art like this as a statement of defiance against those who want to control our bodies and our sexualities to suit their own warped views of humanity.

One thought on “Movie Review – Arabian Nights”