Here are the films that weren’t new in 2024, but they were new to me. Of all my first-time viewings this year, these movies stuck with me.

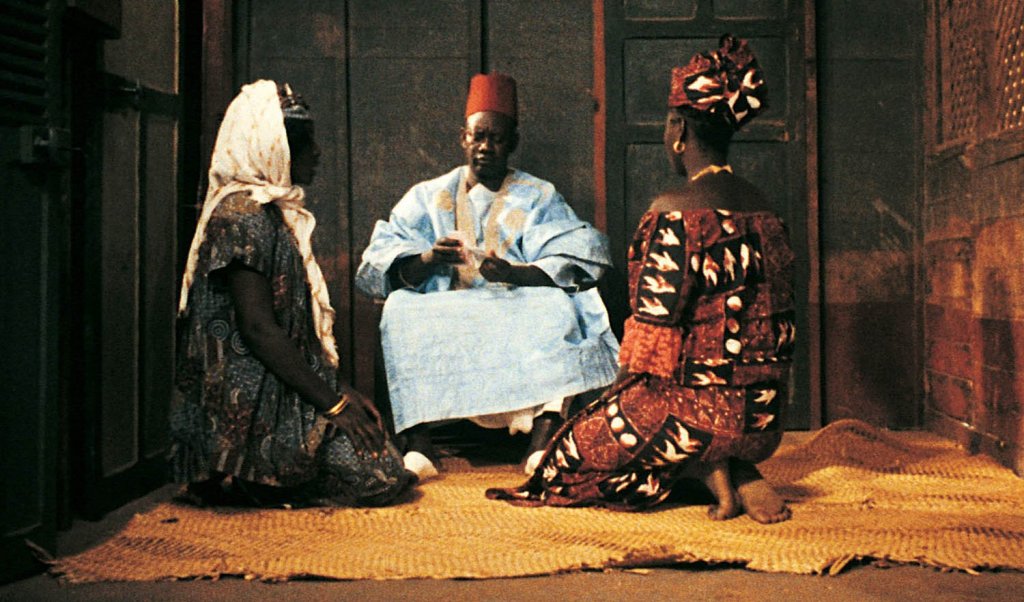

Mandabi (1968, directed by Ousmane Sembene)

Read my full review here

In 2024, I discovered the films of the late Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene. Most of Sembene’s work is focused on the colonial/post-colonial era. He looks at how even when the colonizer has been (mostly) physically removed, their specter remains in social and economic structures. That sounds very academic, but Sembene can make it easy to digest and genuinely hilarious in a film like Mandabi. A Senegalese man receives money from a nephew working in Paris. He’s meant to disperse this money in a specific way to particular people, but once news of the money gets around the community, everyone starts showing up to call in debt or plead their case. If you want an introduction to West African cinema, I think Mandabi is a great jumping-off point and had me cracking up many times.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943, directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger)

Listen to my full review here

I watched some Powell & Pressburger films I hadn’t seen before in 2024, and this was my favorite of them. Made during World War II, this film follows the life of the titular Colonel Blimp leading up to his role in the war that was happening at the time. Throughout this decades-long life story, he falls in love, makes friends, faces enemies, and wrestles with the ideas of “honorable warfare” versus the changing tactics of enemies in the mid-20th century. This film is sharp and cleverly written, and it is unwilling to settle for easy, expected outcomes due to its many storylines. Beyond the writing and great performances, this is a visually gorgeous movie. Powell & Pressburger’s use of color is beyond the standard of the time, and it’s no wonder their pictures captured the attention of so many future filmmakers in their early years.

Babe: Pig in the City (1998, directed by George Miller)

Listen to my full review here

I didn’t expect the sequel to Babe to be such a moving and beautifully made film. Babe must show off his sheep herding talents for profit when debtors call Farmer Hoggett’s farm. The old man ends up in traction after an accident, so Mrs. Hoggett must take the little pig into a city that is a visual amalgam of every major city on the planet. The movie becomes something magical when they arrive at The Flealands Hotel, a locale populated by various other animals with their own reasons for living in this metropolis. George Miller, the mind behind Mad Max and Happy Feet, brings all his full-throttle energy to this affair. In my opinion, the chase scenes in the latter part of the picture are just as good as any car chase in Fury Road. The pathos is incredible; it’s a movie in which an orangutan putting on human clothes actually made me feel like I was going to cry.

Do the Right Thing (1989, directed by Spike Lee)

Read my full review here

I’d always heard and knew this was a great film, but in 2004 I finally saw that for myself. I do think it is dated in the same way as films like In the Heat of the Night or Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? may be. That’s just because the way we often talk about and present anti-blackness in the media shifts and causes previous methods to sound “old-fashioned.” The ideas are all as fresh as ever, particularly Lee’s insights into gentrification. The cast are all-stars: Giancarlo Esposito, Danny Aiello, Samuel L. Jackson, Rosie Perez, John Turturro, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, and a whole host of Black characters actors you will recognize from many other films and tv series. The one weak spot in the film for me was Lee’s acting. He may be a great director & writer, but his line delivery needs a little work. Captures the oppressive heat of U.S. summers perfectly.

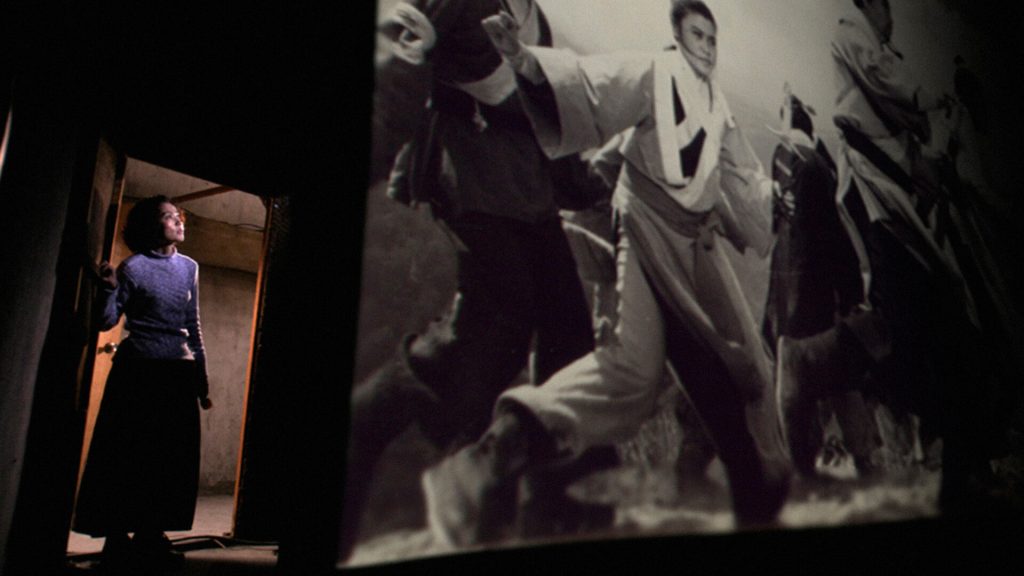

Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003, directed by Tsai Ming-Liang)

Read my full review here

Slow cinema isn’t for everyone, especially people who are used to the faster pace of a Hollywood production. This quiet film visits a Taipei movie theater for the last ninety minutes of the last film it will screen before permanently closing: a wuxia classic titled Dragon Inn. A disabled ticket lady keeps searching for the projectionist to share an extra steamed bun with him, but he’s nowhere to be found. A Japanese tourist seeks a homosexual encounter but discovers the further he ventures into the theater, the stranger it becomes. Two actors from Dragon Inn come to watch it and bump into each other in the lobby. This profoundly subtle film contains so much to say about movies and humans at its slow pace.

Irma Vep (1996, directed by Olivier Assayas)

Read my full review here

Movies about movies aren’t new, but French filmmaker Olivier Assayas made a very interesting multi-perspective take on the medium in Irma Vep. Actress Maggie Cheung plays a version of herself who has been hired to star in a remake of a silent film, Irma Vep. Cheung will play the title character, directed by Rene Vidal (Jean-Pierre Leaud), who is unstable and worsens as production progresses. There are many allusions to French film history, and several characters lament the changed nature of moviemaking driven by the finance industry. Through the affair, Assayas finds humor in his increasingly absurd line of work, but also takes some experimental divergences that have stayed with me. The show was remade (?) decades later as an HBO series of the same name starring Alicia Vikander.

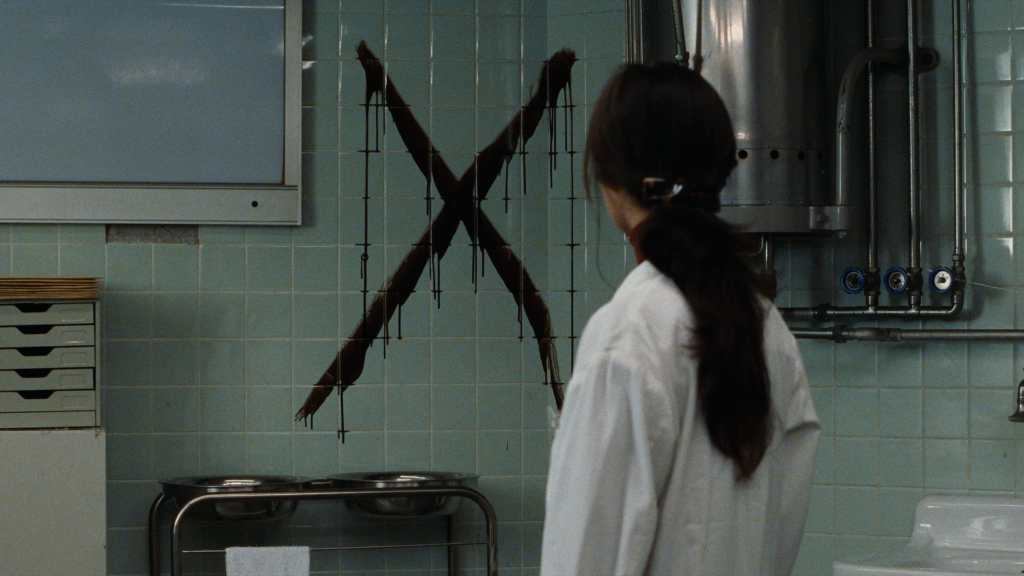

Cure (1997, directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Read my full review here

I’ve been lukewarm about Kurosawa’s Pulse, but his 2024 short feature Chime renewed my interest in his atmospheric existential horror. Cure was the movie that made a name for Kurosawa. Released the same year as Se7en, I found Cure more engrossing than that film. They both traffic in the same dark territory, where it’s not really about finding the killer but more about the detectives involved staring into the void. Detective Takabe is trying to solve a series of strange murders where the perpetrators appear to have been compelled against their will to kill. Eventually, an odd young man is found with connections to every crime, but this is only the start of Takabe’s problems.

All That Jazz (1979, directed by Bob Fosse)

Listen to my full review here

Bob Fosse made an audacious film here. This semi-autobiographical fantasy follows choreographer/director Joe Gideon as his life becomes full of work & personal life stress. He is assembling his next Broadway musical while editing a feature film and fooling around behind his partner’s back. Gideon keeps having fantasies where he’s visited by the Angel of Death and is eventually hospitalized for severe angina. Fosse leans into his toolbox of skills to create a wild vision of mortality, health, and death. There’s even a dance sequence having him go through the five stages of grief. His dreams become more hallucinatory the closer he gets to death and culminate in a wild, psychedelic closing number.

Design for Living (1933, directed by Ernst Lubitsch)

Read my full review here

In the pre-Code era of Hollywood, U.S.-produced films were able to talk about sex in a far more sophisticated way than you might imagine. Two friends meet the charming Gilda on a train ride to Paris. Both men fall in love but promise the other they will forget about her to maintain their friendship. Gilda decides she will live with the men, but purely platonically, serving as a muse for their respective arts. One man eventually leaves when one of his plays is set to be staged in London, which causes a sexual relationship to spark with the remaining two. Design for Living is fresh, still funny, and presents a modern story. Ernst Lubitsch was a filmmaker who never wanted to talk down to his audience; this film is a perfect example. It’s a sex comedy for adults that is both entertaining and very authentic.

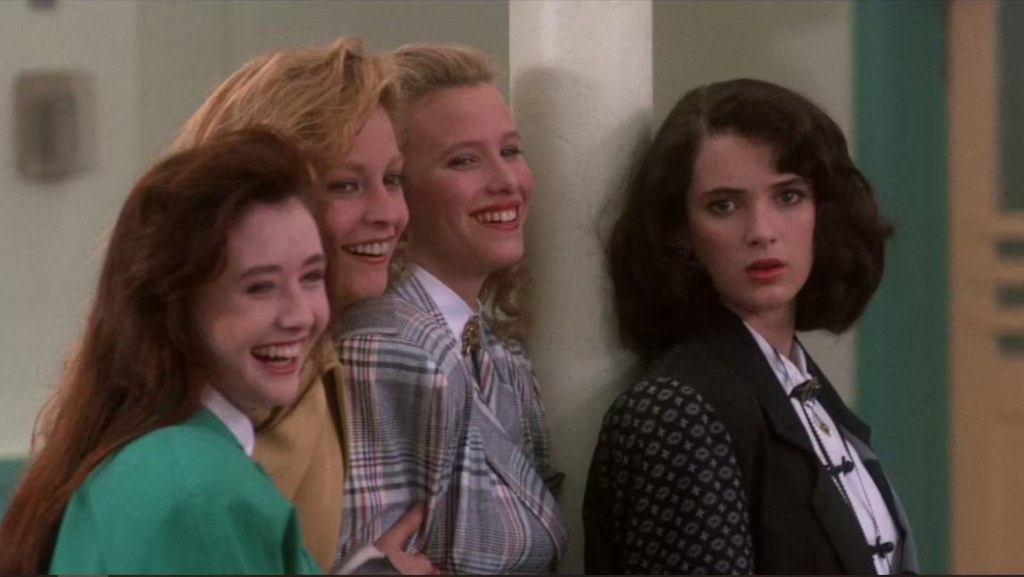

Heathers (1989, directed by Michael Lehmann)

Read my full review here

The best Winona Ryder performance is right here. Before watching Heathers, I wouldn’t say I was ever that impressed by Ryder. She did fine in all the roles I saw her in, but nothing that ever amazed me. After reading Michael Lehmann’s script, it made sense why she lobbied so hard to get cast as the lead. The role of Veronica is a perfect fit for the then-teenage actress. Ryder is so effortlessly charming, especially regarding her chemistry with co-star Christian Slater. The scenes between these two are an utter delight to watch. Lehmann also delivers a biting satire about America in the late 1980s, especially the privileged and their treatment of anyone they deem an Other. The late great Shannen Doherty also does a fantastic job as the diabolical Heather Duke.

The Spirit of the Beehive (1973, directed by Victor Erice)

Read my full review here

This Spanish film captures the melancholy nature of being a child so perfectly. Child actor Ana Torrent delivers a quiet, impactful performance as little Ana. The girl watches Frankenstein at a screening in her village. It haunts her for weeks and months after, and she becomes fixated on death. Her parents are perpetual in their own heads, and her older sister just antagonizes her. Director Victor Erice is commenting on what it’s like to be a child while also attempting to talk about the rise of the fascist Franco regime which came to power in the year the film is set, 1940. The beehive becomes a metaphor for Spain at the time, full of activity but very little actually happening. It’s a visually and emotionally stunning work of art.

Au Hasard Balthazar (1966, directed by Robert Bresson)

Read my full review here

Balthazar the donkey is just an animal; he can be nothing more than that. Yet the humans he encounters always want more from him than he can give. Farm girl Marie loves Balthazar and shows him care he never gets from anyone else. The world is a violent place for both girls and donkeys, and throughout the film, they are treated with great cruelty. Bresson has recreated the world on film. This is a piece of art that resonates on a near-biblical level. It also feels like a film that must have influenced Bela Tarr (more on him below). Bresson might be a hard pill for some audiences to swallow. He doesn’t call his performers “actors” but “models.” This is reflected in the often stony performances. Bresson isn’t after flashy acting but a certain spark in people that makes us forget we’re watching a story and causes us to believe in this world.

Mikey and Nicky (1976, directed by Elaine May)

Listen to our full review here

With a Christmas release in 1976 that bombed, Mikey and Nicky is a film that didn’t get its due initially. The brilliant Elaine May directs consummate performers John Cassavetes and Peter Falk to tell the story of two old friends across one complicated night. Nicky stole money from a connected man. The mob has contacted Mikey about luring his pal out of hiding so they can exact their revenge. There is a lot of improv here, something of May’s specialty, and she couldn’t have two better actors to work with. The camerawork can make this feel like a documentary at some points, especially with how chaotic the scenes will get. It’s the emotions between the lead actors here that pull me in. As the traitorous Mikey, Falk is constantly at odds with himself, knowing that he will be targeted if he doesn’t betray his buddy.

The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Read my full review here

We like to think that older films don’t have the same emotional resonance a modern picture would, with sound, color, digital cinematography, and all the other advancements since film began. Carl Theodor Dreyer proves those voices wrong with his nearly 100-year-old film, The Passion of Joan of Arc. Meticulously researched, the film presents Joan’s trial by the French clergy that sought to stomp out any inspiration the public might get from the teenager’s rebellious words. Dryer shoots this unlike anything you’ve ever seen before, making the faces of the torturers and the victim the focus of many close-up shots. Renée Jeanne Falconetti is stunning as Joan; she was a woman with her own mental health issues, and I think she brought a lot of that into the performance of the delusional Joan. A perfect example of a film that doesn’t feel aged a bit.

Seven Samurai (1954, directed by Akira Kurosawa)

Listen to my full review here

Akira Kurosawa will probably never be a director I love as intensely as so many do. But I do appreciate his films for being groundbreaking and shaping how we perceive movies today. I had never seen Seven Samurai until this year, and it quickly jumped to the top of my list. In this film, Kurosawa builds a structure that will be directly copied, but many other tropes here will become part of the global cinematic language. A village is dealing with rapacious, murderous bandits. They send some of their own out to hire ronin, samurai without masters who will work for money. A ragtag group is brought together with a dedicated leader, a quiet loner, a young greenhorn, and even a chaotic wildcard. This movie never feels like a long runtime; Kurosawa always ensures something is happening to keep the audience deeply engaged.

The Double Life of Veronique (1991, directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski)

Read my full review here

In this hypnotic film, Kieślowski plays around with notions of the Self about two identical women with nearly identical names who never directly meet. One is Polish, one is French. They have several connections between them, mainly in where their interests lie. The film’s first half is about the Polish Weronika, while the second deals with the French Veronique’s sudden notions of grief & sadness, which she can’t explain the origins of. Both women are deeply enamored with music and have an unexplainable sense that they are not alone in the world. The Double Life is a trance-like movie that uses its sepia/yellowed color palette and dreamlike cinematography to evoke a sense of the mysterious. Kieślowski is asking us to question our own lives and identities.

The Conformist (1970, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci)

Read my full review here

Fascist regimes work when the most mundane, mid-level people keep doing the work. The Conformist is about one of those people, Marcello. He’s a bureaucrat with remnants of an intellectual streak that’s been tamped down by an intense desire to be seen as “normal.” Mussolini’s secret police come to him with a job; he must assassinate his former mentor, who lives in exile in Paris. The story here feels sadly relevant to the ongoing rise of fascism in the West, which is only made possible by the worker bees on the ground. If the fascists lose access to the infrastructure, they would fall apart quickly. Bertolucci uses a lot of art styles from the era he’s portraying in the look of the film, specifically art movements that were popular among Italian fascists. The result is a world that looks heightened and abnormal, pushing back against Marcello’s idea that if he conforms, he will be accepted by the majority.

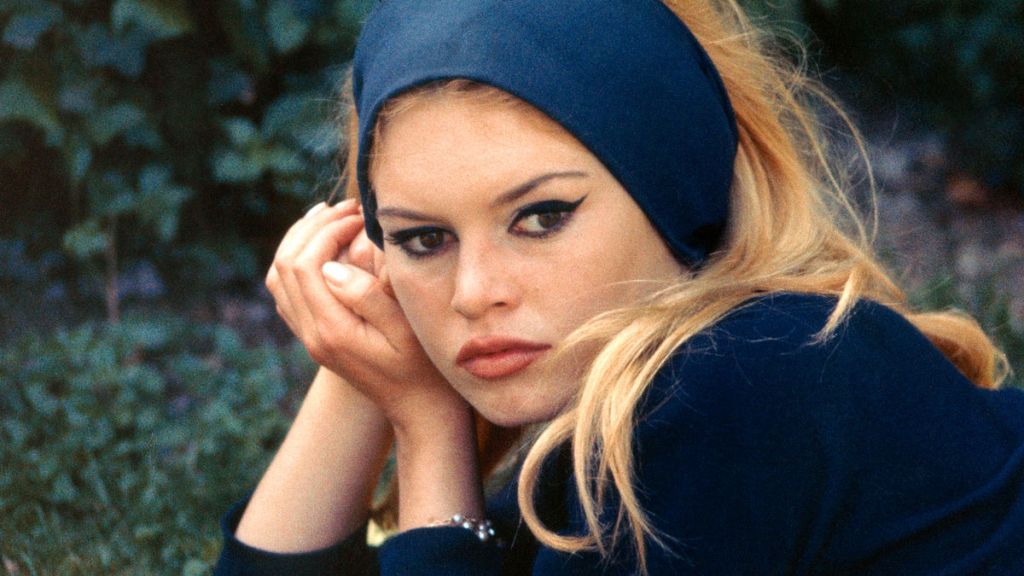

Contempt (1963, directed by Jean-Luc Godard)

Read my full review here

It is stunning to me that Contempt was made as early as 1963. This feels like something from the 1970s and was a big influence on the films of that decade. French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard tells the story of a screenwriter whose relationship with his wife frays until it snaps. The breaking point comes when an American producer hires the writer to fix a script for a film about Homer’s Odyssey. His wife becomes an object of lust to the producer, and her husband passively pretends he sees nothing. Godard manages to take the themes of the Odyssey, particularly around Odysseus and his wife. There are clashes about the film’s direction from its director, Fritz Lang, playing himself. Contempt feels like a French New Wave that went far beyond the aesthetics we expect from them. This is a refined piece of cinema that feels larger than life.

Tokyo Story (1953, directed by Yasujirō Ozu)

Listen to my full review here

Ozu is the master of quiet melancholy. Here, an elderly couple travels to Tokyo to visit their adult children. They are proud of how far their kids have come from a humble rural life. Yet, the speed and intensity of modernity proves a lot for the couple. Their own children feel slightly annoyed at having to entertain and look after their aging parents. Tokyo Story is Ozu’s lament over what Japan lost following World War II and the American takeover of the country. As the other half of Japan’s cinematic soul from Kurosawa, Ozu can communicate so much in a quiet scene between an old man and his young daughter-in-law, left a widow by the war. They can just look at each other or gently pat each other’s hands, and we learn so much about family and love.

The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover (1989, directed by Peter Greenaway)

Read my full review here

I was blown away by how good this movie was and kicking myself that I hadn’t watched it sooner. I was unfamiliar with Peter Greenaway’s films, but I am intrigued after this. A London mob boss has invested in a new French restaurant, fashioning himself a type of foodie while everyone around him can see he’s a brutish oaf. His nearly mute wife strikes up an affair with a patron, and kitchen staff help them hide it from the husband as best they can. The grandeur of this film cannot be understated. It is an opera without much singing. It is an epic tragedy that will break your heart. As the wife, Helen Mirren gives the best performance I have ever seen from her. A genuinely perfect movie that I want to watch many more times.

The Films of Pier Paolo Pasolini (Acattone, Mamma Roma, The Gospel According to St. Matthew, Theorem, Salo, etc.)

This year, I watched nine films written & directed by Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. I found him to do an excellent job of blending the profane with the holy, one of his favorite themes to bring to the table. He produced works of extreme beauty (St. Matthew) but also profound evil & cruelty (Salo, or 120 Days of Sodom). My favorite of his works that I saw was Theorem, a nearly wordless film with Terence Stamp as a seductive figure that fucks his way through an entire bourgeoisie family who then go through a mental collapse when he leaves. Pasolini was able to turn poetry into cinema.

The Films of Mike Leigh (Life is Sweet, Naked, Secrets and Lies, Happy Go Lucky, etc.)

Mike Leigh is the working-class director I’ve been needing. His films, almost always set in Manchester or London, center on regular people living complicated lives. Life is Sweet is a film about how complex families can be and how to sometimes embrace the chaos. Naked is a stunning rant from someone looking at what Margaret Thatcher did to the UK. Secrets and Lies is a tour de force with a fantastic lead performance. Happy Go Lucky shows us why good teachers matter more than most things. Through all his work, Leigh finds joy in lives that often go overlooked. He also isn’t afraid to show us the dark side of human beings but refuses to condemn them to only being that way.

The Films of Bela Tarr (Damnation, Satantango, Werckmeister Harmonies, The Turin Horse)

Hungarian filmmaker Bela Tarr makes imposing, unwieldy films about similarly complex ideas. His seven-hour Satantango is the longest film I have ever watched, and I fell into a trance while watching it. Each of his movies is about being Hungarian and alive in the modern world. The environments are often decayed or in ruins. People plot & connive, typically unbothered by the suffering they cause another. Yet, there are always characters who are searching. They rarely find what they are looking for. Damnation is a classic noir story that is done in such a unique style. Werckmeister Harmonies is a harrowing fable about the mob. The Turin Horse intimately portrays humanity’s end (it’s a two-person movie) yet feels grand in scope. You must set aside time, but Tarr’s work is worth it.

The Films of Frederick Wiseman (Titicut Follies, Juvenile Court, Law and Order, Welfare, etc.)

Documentarian Frederick Wiseman has chronicled every institution you could imagine in the United States. While he is fascinated with how these bureaucratic machines operate, he is equally concerned about their effects on the humans they are said to serve. Titicut Follies, his debut film, showed how violent mental health hospitals in the States had become. Juvenile Court watches as child after child is failed by a system that claims to be there to help make their lives better. Welfare is similar, but even larger in scale, a nearly three-hour epic about the people coming for help in a New York City welfare office. Wiseman captures people at their purest – their emotions flow like water, and we can see mythic archetypes within them. The pained lament of a young man about to be indefinitely sent to a work camp. A Black woman who just wants a place to sleep broke down from running from office to office. A mentally unwell veteran spitting hate at a Black security guard who is trying to keep his cool. Wiseman has shown us America. We have to ask if we’re brave enough to look.

One thought on “My Favorite Film Discoveries of 2024”