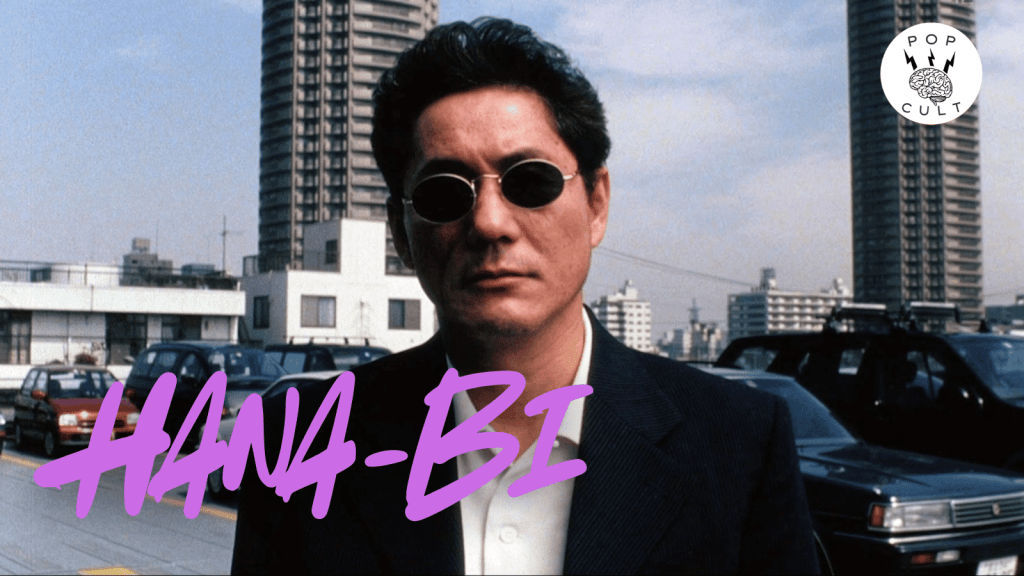

Hana-bi (1997)

Written and directed by Takeshi Kitano

One of my favorite things as a film fan is coming across a filmmaker doing something all their own. No film exists in a vacuum, so you’ll always see influences from others. But how that filmmaker mixes their ingredients makes all the difference. Takeshi Kitano started his media career as a comedian and TV host in the early 1970s. It was Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, in 1983, where Kitano made his feature film debut. It was a non-comedic role as a Japanese soldier who brutalized Allied prisoners. In 1989, he made his directorial debut with Violent Cop, a neo-noir film. And then it was this movie, translated into English as “Fireworks,” that won Kitano the Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival, only the third Japanese director after Akira Kurosawa and Hiroshi Inagaki to win the honor.

Things begin on a down note as Yoshitaka Nishi (Kitano) is forced to retire from his job as a police detective following a botched arrest that leaves one of his colleagues dead and two others severely injured. Now unemployed, Nishi spends most of his time caring for his ailing wife, Miyuki, who has been diagnosed with leukemia. Nishi is forced to take a loan from the yakuza to pay for his wife’s care.

Nishi visits one of his now-paralyzed ex-colleagues, Horibe, who is paraplegic. His wife and child have left him, and he’s slipped into depression, hinting at suicide. Nishi picks up on his friend’s interest in painting and sends him supplies to get Horibe to make something beautiful. As the yakuza pressures Nishi to pay, he pulls off a bank heist, which will only sink him further into the trouble he’s accrued for himself.

Hana-bi is such a unique experience. It has familiar Western cinematic elements with the disgraced cop and all the noir-ish bits. But Kitano has no interest in retreading well-worn territory. He takes what is familiar to us and makes it his own. Nishi feels like an overpowered character at times. He is able to pull off so many things: robbing a bank, repainting a cab into a police car, and killing the yakuza that come after him.

However, the thing that matters the most to him is impossible for the ex-cop to do: save his wife from dying. We also learn their daughter died years prior, and he’s left helpless in that regard, too. Kitano has mastered that sense of tragic fate, undermining the Dirty Harry archetype. There are bad things that happen in our lives that we simply cannot avoid. We must endure them. Kitano has taken the Western “cop revenge” trope and turned it on its head, making us sit with our everyday powerlessness against those primal elements of life that will defeat us.

There are moments of action in Hana-bi, but they are the exception, not the rule. Kitano wants to examine the consequences of such violent bravado. What happens to the guys in a John Woo movie after they jump through the air in slow motion, emptying their handguns? Nishi’s violence towards his antagonizers is not drug out. He’s accosted by yakuza thugs at a noodle shop and jabs a chopstick through one of their eyes in a moment that zips by so quickly. Kitano refuses to dwell on it.

Instead, we spend most of the film with Nishi and Miyuki. Once he gets the cash from the robbery, they go on the lam and do silly, stupid things. They fly a kite on the beach. They find reasons to laugh at life. Nishi wants nothing more than to ensure his wife’s final months alive are as joyous as possible. She does not need to know anything he’s done to make this happen. The lies he tells are barriers set up to protect her from the aggression he can feel coming his way.

The film becomes this loop of ordinary everyday moments between the couple, followed by brief bursts of violence from Nishi. Miyuki tries watering dead flowers, which elicits laughs from a man watching. Nishi snaps and brutally beats the man until he blacks out. Kitano chooses to make Nishi a near-silent figure and doesn’t have his own expressions to lean back on. The director had been in a motorcycle crash, which left much of his face paralyzed. Kitano uses that blankness to make Nishi an enigma to the audience. We think we understand him, but can we ever really?

The conclusion an audience should come to is that Nishi is a psychopath. He uses “protecting his wife” as a reason to be a violent brute. Look at the excuse of so many reactionaries in the States to justify their violence and gun lust. They “need to protect their families” without any regard to how carrying a gun around with you everywhere you go is a type of provocation. Are their loved ones really in danger, or is this about the neuroses of the man, feeling emasculated for whatever reason he’s been fed? It doesn’t sound like Nishi is a character that Kitano would say we should emulate.

That’s where Horibe comes in. I kept anticipating he was going to kill himself. A scene early in the film shows the disabled man letting the tide begin to rise on his wheelchair. But he doesn’t, and the painting materials are used to create a series of pieces. They all share that the people’s faces are replaced with flowers (roses, iris, daisies, etc.).

These images become the camera’s focus throughout the picture, slowly zooming in or out. I found the pictures psychedelic and captivating. Alongside the gorgeous landscape cinematography, they elevate Hana-bi into a stunning piece of visual art. Horibe is also the foil to Nishi. He could easily lash out at the world, but instead, he’s trying to remind himself that beautiful things still exist. No matter how ugly his life has become, he can still find beauty around him.

You are not likely to see anything like Hana-bi anytime soon. Kitano has pushed away all the narrative expectations audiences have come to rely on. You are forced to engage with the picture rather than view it passively. Many things go unexplained, emphasizing what interests the director in this story and as a sign of respect to the audience. Kitano doesn’t need to explain everything because that’s how life is. He removes all the fat and leaves us with a lean, profound piece of cinema.

One thought on “Movie Review – Hana-bi”