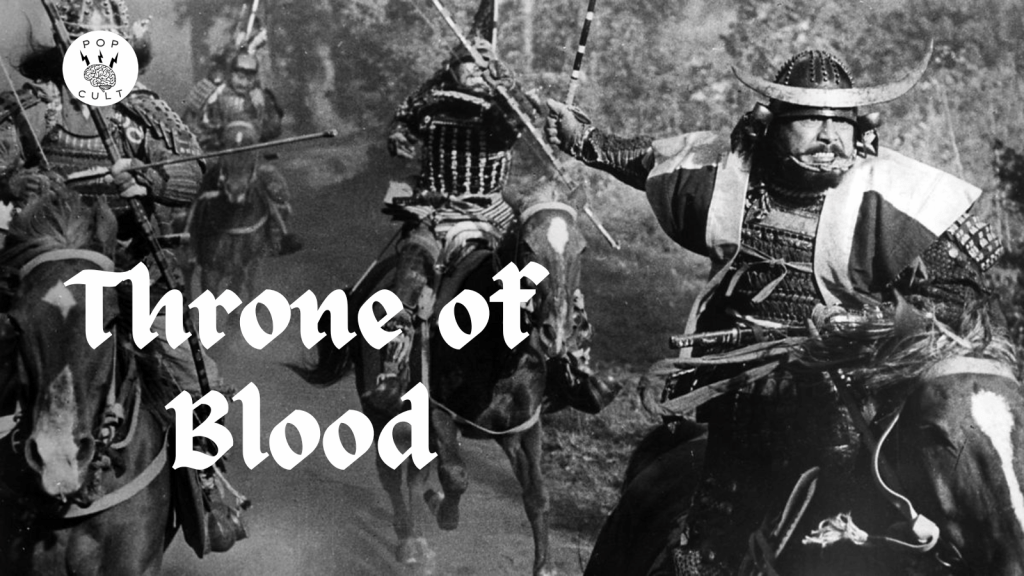

Throne of Blood (1957)

Written by William Shakespeare, Shinobu Hashimoto, Ryūzō Kikushima, Akira Kurosawa, and Hideo Oguni

Directed by Akira Kurosawa

I could have gone with more traditional adaptations of MacBeth, but I wanted to see how Kurosawa interpreted the work. I was also interested in learning how far back Japan’s history with Shakespeare’s work went to understand how well-known the play was. Shakeapeare’s plays arrived in Japan during the Meiji Restoration when power was reconsolidated under the Emperor. If you watch Shogun, it is the beginning of the Tokugawa Shogunate, which ended with the Meiji Restoration. It was marked by the opening of Japan’s borders to foreign influence in a way that had never been seen before.

Japanese culture under the feudal system was seen as obsolete and expensive to upkeep, so castles and shrines were destroyed by order of the Emperor. Samurai were outlawed, Buddhism was condemned, and cremation was banned. In this world, the Bard’s plays made their way into Japanese hands. The first recorded Japanese staging of a Shakespeare play (The Merchant of Venice) happened in 1885. By 1875, Seiyo Kabuki Hamuretto (A Western Kabuki Hamlet) was published, beginning a trend of adapting Shakespeare, nicknamed “Sao,” into a context that the Japanese could better relate to. By the time we get to Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, Shakespeare was widely read & known throughout Japan.

General Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) and his samurai comrade Miki (Akira Kubo) are traveling through the Spider’s Web Forest, returning to the castle of their lord Tsuzuki, having helped defeat his enemies. They encounter an evil spirit in the woods. The Spirit taunts them with visions of the future, saying Washizu will become lord of the Northern Garrison while Miki and then master of the castle they are headed to. But the Spirit also says Miki’s son will become lord of the castle, which confuses the men. At home later, Washizu discusses the prophecy with his wife, Asaji (Isuzu Yamada). Her husband has been rewarded with the North Garrison for his service to his lord, so she sees this not as a prophecy but as a series of steps to attain greater power.

If you’re familiar with Macbeth, you know where this goes, a descent into murderous plots and the haunting guilt that ripples through the perpetrators. Friends become outright enemies, warring over power and revenge. The story asks: Was this a prophecy, or were these Washizu/Macbeth’s active choices the whole time? The Spirit acts merely as an agitator, stirring up trouble because it can see into the hearts of these people. Or maybe the Spirit is a student of human behavior and knows that all men with power do these things repeatedly.

The Spirit is one of Kurosawa’s most brilliant adaptations, taking the three witches of Macbeth and transposing them into a singular figure from Noh drama. Noh is a form of dance theater involving many masks worn by the same actors. The Spirit wears various masks throughout its appearances in the film and is in this theatrical form’s style. Noh is centered around the Buddhist idea of impermanence, that all states of being are fleeting. If you are content, it is only a matter of time until you are discontent, and vice versa. This reminds me of the Medieval European idea of the Wheel of Fortune, that life was a series of ups and downs regardless of what the individual did. Noh is also where the film’s score comes from, relying on flute and drum.

Washizu slides so easily into the idea of murdering his lord, plotting with his wife on how to do it. He expresses a lot of apprehension, but it’s clearly not authentic as he so quickly kills Lord Tsuzuki. The murder occurs while he is a guest in his lord’s home, and he pins it on a guard, which creates chaos throughout the palace. There’s never really a moment where Washizu genuinely stays his hand. He often acts impulsively, driven by the promise of power over the world he knows.

The moment of no return for me has always been Washizu’s/Macbeth’s betrayal of Miki/Fleance, his friend. It is the most disturbing example of the protagonist’s moral decay. It’s one thing to kill your lord in a feudal system, but your friend, your comrade, is a sign of a truly grotesque person. Miki fought alongside this man; they were genuinely friends, but the prophecy hints that Miki’s son would usurp Washizu one day. Paranoia, ruthlessness, and all of these transform a person into something inhuman, unable to connect with others. Ironically, it is the killing of Miki that secures his son’s overthrow of Washizu, something the spirit delights in as it knew this was how it would be all along.

To have total power means you will inevitably fall. This is why hyper-individualism is a dead-end ideology. Great things are not accomplished by singular “great men;” they are achieved through collective labor and collaboration. The moment power is seized by strong-arm individuals, they begin a process under which they will lose that power, which we see historically ends up being intensely violent. Many suffer simply for the selfish whims of a lone man.

Unsurprisingly, Kurosawa delivers a visual feast here. The opening shows a desolate place in ruins, and we go back to when a palace once stood there to learn the story of its destruction. Thick fog is a metaphor for time, pulling us back through the ages. The forest is presented as a nightmarish labyrinth where the spirit world has more power than mortal men, leading them on wild goose chases. One of the best visual moments of the whole film is the famous “moving forest” sequence where Washizu looks out from his palace and sees the trees moving towards him, something from the prophecy. Kurosawa cuts to a behind shot, and we see Miki’s son leading troops with the very trees as cover.

I don’t think you could find a better adaptation of Macbeth, even one more culturally faithful to the original. This, to me, is the magic of Shakespeare; his work is not about Western values but universal human flaws and challenges. He understood the broken nature of humanity’s hunger to control everything. While not a Buddhist, the Bard would have been right at home with the theme of impermanence. Never believe you have total control of anything. You live in the whims of the universe, and you just have to hope you find some contentment in your life.

One thought on “Movie Review – Throne of Blood”