Henry V (1989)

Written by William Shakespeare & Kenneth Branagh

Directed by Kenneth Branagh

Many millennials’ earliest film experience with Shakespeare was probably Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet, which we will review soon. However, that was not the start of the Shakespearean renaissance in film. While the Bard’s plays have always been popular in one form or another, Kenneth Branagh’s work produced several of the most complete film adaptations of the stage plays. Henry V was Branagh’s directorial debut, followed by four more pictures (Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet, Love’s Labour’s Lost, and As You Like It).

The Chorus (Derek Jacobi) walks through an empty film studio, delivering a prologue to set the stage for our tale. In the early 15th century, religious leaders attempt to distract the young king Henry V (Branagh) from passing a decree to seize some of the Church’s property. Instead, they talk him into invading France instead. The Archbishop of Canterbury produces a convoluted document wherein he says it proves that Henry is the rightful heir to France. More support is garnered among the nobles, and England declares war on France.

While this happens, John Falstaff lies dying in Mistress Quickly’s Inn. His friends gather around to talk about the good times. Those times include when Henry was just a prince, and Falstaff served as a mentor figure to the future king. Now that Henry sits on the throne, he has denounced his old friends as degenerates. The two main threads of this story are the death of Falstaff and Henry’s successful but tragic campaign in France.

One of the smartest creative choices made by Branagh here is to incorporate extracts from Henry IV Part 1 and Part 2. These are scenes where young Henry interacts with Falstaff. In the text of Henry V, Falstaff is never seen; he is just spoken about by his friends. This is an essential piece for an audience unfamiliar with the background of Henry & Falstaff. An earlier line from Falstaff in those plays, “Do not, when thou art King, hang a thief,” is assigned to Bardolph, one of their mutual friends, when he’s caught by Henry’s men and the king must make a shattering decision.

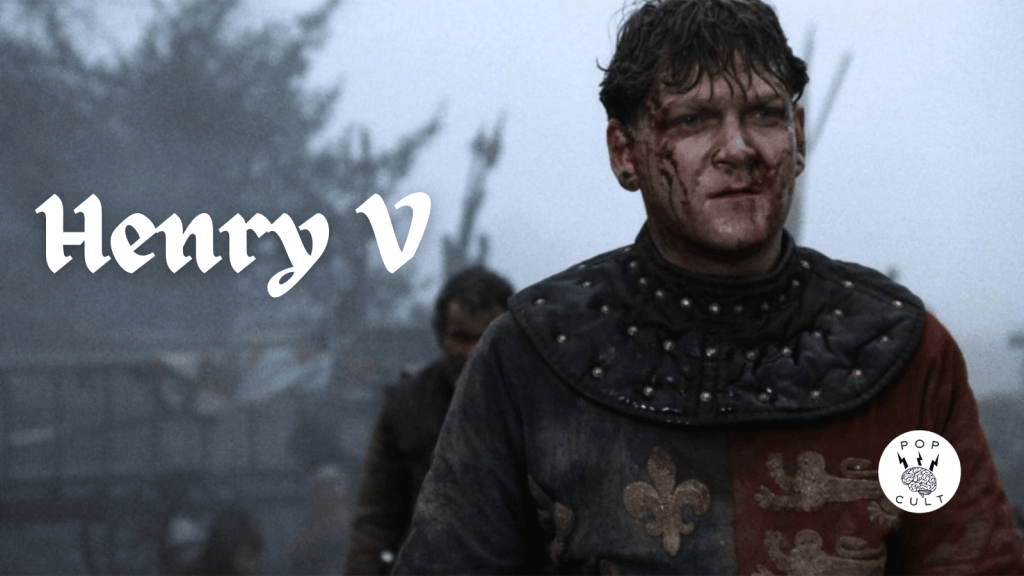

There’s also a stylistic choice made where older productions’ cleaner look is pushed aside to present something with a bit more grit. The famous Battle of Agincourt occurs on a rain-soaked field, with the soldiers caked in mud and blood. This helps in underscoring the brutal cost of Henry’s decision to pursue war with France. He surveys the aftermath and finds so many good men dead in his pursuit of conquest. The scenes of the inn patrons aren’t played as comedic relief but more poignant as they pay tribute to their dying friend.

I find myself in conflict with the text, and that is felt by other portions of the audience. The depiction of warfare in this play comes across as dangerously light. It reads of that archaic notion that war is a grand rite of passage for young men, which indeed fell out of style after the apocalyptic, industrialized warfare of World War I, though war has always been a horrible thing. The most relevant reading is that Shakespeare sought to portray war in all its complexity as he would with any other subject or character. There’s an acknowledgment that war costs lives and the abandonment of morality.

Henry is a perfect example of this, switching his view of the war multiple times throughout the play. During Harfleur, his words are dark, more menacing, speaking of “rape and pillage.” Parallel this with the famous St. Crispin’s Day speech where the king frames the war as a grand patriotic glory for which these soldiers will be remembered with reverence forever. I think the role of Henry’s old friends is meant to be a reminder that he has compromised so much of his beliefs & morals to get here.

What I got from this viewing of Henry V was a study of those who lead men into war. There were passages from Henry that genuinely disturbed me, where he spoke about what his men would do as if they were acceptable, that wartime meant a suspension of morality. In threatening the Governor of Harfleur, he states:

The gates of mercy shall be all shut up,

And the flesh’d soldier, rough and hard of heart,

In liberty of bloody hand shall range

With conscience wide as hell, mowing like grass

Your fresh, fair virgins and your flowering infants.

These don’t seem like the words of someone I am meant to admire. And this tracks. Shakespeare was never averse to making a morally questionable person the center of his narratives – Titus Andronicus, Macbeth, Hamlet, Iago, etc.

I was wildly thrown off by the conclusion of the film, where Henry has a strangely sweet scene with Katherine (Emma Thompson), daughter of the French king Charles VI. Henry has been promised this woman in a diplomatic marriage but goes about explaining that when he professes his love for her, he, in turn, declares his love for the French people and vice versa. The Chorus wraps up the play by explaining how England would lose France by the end of the next generation, with Henry’s son, Henry VI, being responsible for it.

This epilogue was perhaps the ultimate point Shakespeare was attempting to make. All of this effort, all of these lives, all of this patriotic bravado was spent to gain control of land that would be lost in a matter of decades. Henry’s St. Crispin’s Day speech was meaningless beyond hyping up his soldiers to run headlong into battle to die. Initially celebrated on 25 October, the holiday is no longer celebrated and is only remembered as the event mentioned in this speech. Hence, these soldiers’ sacrifices were ultimately forgotten, and the very thing they had conquered was lost.

In our contemporary age, where wars and rumors of wars abound, reflecting on the impermanence of military conquest would do us good. Buzz surrounds the sacking of Canada or Greenland, with even some U.S. Liberals openly saying that adding Canada would be a boon for Democratic electoralism. It casts a dark shadow over our future that the opposition party is so welcome to the idea of military seizure of other lands. True postcolonialism is still far from our grasp because we haven’t collectively reckoned with its fundamental horror.

The last vestiges of Palestine are swallowed up by the Israeli Occupation; its people are told they will be permanently exiled. The Ukrainian people are watching as a knee is bent to the invader while they are led by a feckless fool who bit the poisoned apple called U.S. assistance. All around me, I see people suffering at the hands of men who fail to lead and seem unable to see beyond the girth of their egos. Mass media will, of course, sell the idea of war as good, but never a war for the people, always ones where they are placed at the center of the battlefield.

I don’t believe Henry V was a good leader. He was fooled by the Church into letting so many of his friends and subjects get devoured by war. He betrayed the values his mentor Falstaff had sought to cultivate within him. The very thing he burnt up all these treasures for would slip through his son’s fingers. As another Shakespeare play says:

It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

One thought on “Movie Review – Henry V (1989)”