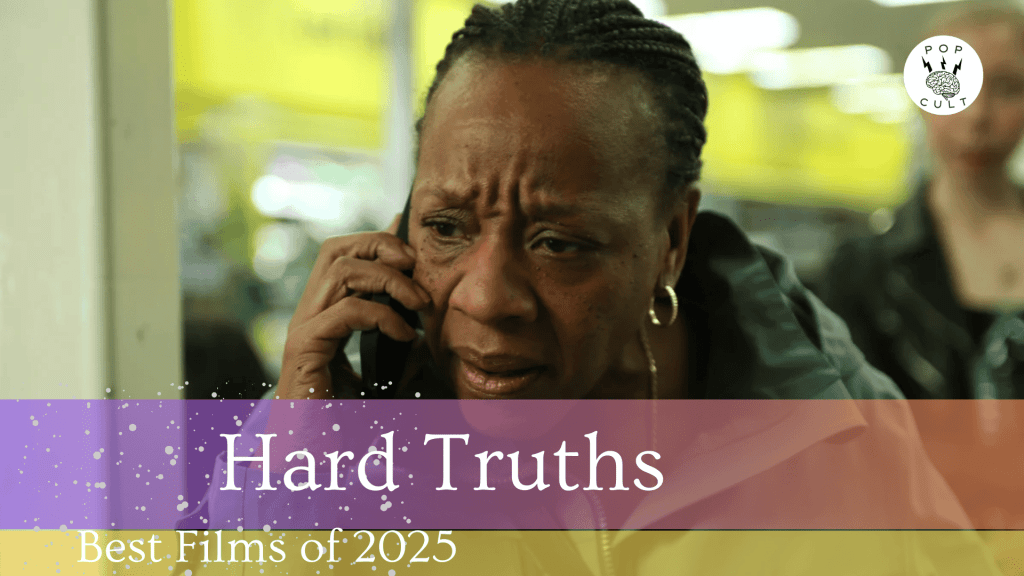

Hard Truths (2025)

Written and directed by Mike Leigh

In 2024, I did a deep dive into the work of British filmmaker Mike Leigh and fell in love. He has a profound love of humanity, and it comes across in his choice to tell grounded, slice-of-life stories. At age 82, he has given us his latest film, Hard Truths. This re-teams him with Marianne Jean-Baptiste, whom he previously worked with in the wonderful Secrets & Lies. As with all of Leigh’s work, he shows a trust in his actors through the use of improvisational techniques and respects the intelligence of his audience by never passing judgment on his characters. This is a film about difficult people and a refusal to stop seeing them as human beings deserving of dignity; something that feels particularly challenging in our current moment, but also something people have grappled with throughout history.

Pansy (Jean-Baptiste) is a middle-aged Black British woman whose life is shaped by anger, anxiety, and a relentless need for control. Estranged from most of the world around her, Pansy lashes out at everyone who crosses her path, especially her long-suffering husband and son. In contrast stands her sister Chantelle (Michele Austin), whose warmth and emotional openness highlight the life Pansy might have had if she were capable of vulnerability. As everyday encounters accumulate—shopping trips, family gatherings, small social interactions—the film patiently reveals the roots of Pansy’s behavior in unresolved trauma, building toward an unsentimental but deeply human portrait of a woman trapped by her own defenses and the painful truths she refuses to face.

It might seem easy to lump Pansy in as another “Karen,” the Western stereotype of the irritable woman. It’s hard to scroll through social media without encountering multiple videos of a middle-aged woman losing her temper in a customer service setting. The road rage incident is the milieu of the “male Karen,” in case you’re wondering; an encounter with a far higher fatality rate than any Karen confrontation. It is easy to dehumanize these people through the filter of a screen, knowing nothing about them as human beings. I think this says far more about the viewer, who sees a person in distress and instinctively mocks them. Yet people should still be held accountable for how they treat others. It’s not a problem with an easy solution, which is precisely why it makes such fertile ground for Leigh to explore.

In his 2008 film Happy-Go-Lucky, Leigh focused on the dynamic between a perpetually upbeat kindergarten teacher and her deeply misanthropic driving instructor. Pansy feels like someone who could have given that driving instructor a run for his money. From the moment she is introduced, we are treated to a ceaseless barrage of negativity and chastisement. Nothing her family does is ever correct, and she finds herself hiding from the outside world, terrified even of her own fenced-in backyard. There comes a point where she resigns herself to her bedroom, refusing to come out from under the covers. Grumpiness becomes a symptom of something far worse: a quicksand depression that turns Pansy into a void emptied of all joy.

Leigh moves beyond the crusty Scrooge cliché and counters Pansy with her sister. Chantelle is a hairdresser with two daughters who are navigating their own struggles in work and life. While the director hints at why Pansy and Chantelle have such different worldviews, he never definitively explains it. That is the point. Some people experience the same circumstances yet emerge as entirely different people. That’s part of the mystery of being human; none of us fully understands consciousness or how it operates. We stumble in the dark, trying to establish patterns we hope will provide meaning. It’s a noble pursuit, and maybe one day the chaos of existence will make sense. In the meantime, we have another tool, one Chantelle demonstrates beautifully throughout the film: empathy. She may grow frustrated with Pansy, but she never stops loving her or making sure she knows she belongs.

Our two leads anchor a cast that feels completely and wholly lived in. This is Leigh’s signature, and it’s what draws me back to his work again and again. These kitchen-sink dramas aren’t concerned with melodramatic twists, and resolution is not something that often happens in real life. Leigh’s stories are slices; segments of larger lives the audience is not permitted to fully observe. The same is true of the people closest to us. One day, someone we love will die without ever knowing what became of the others. We don’t often think about this, yet it is one of the most defining aspects of being human. Instead, we develop anxieties and neuroses.

That is ultimately what has happened to Pansy. She has become so calloused and bruised by personal trauma and the suffocating void of Western modernity that she has chosen to refuse the responsibilities of being human. We owe everyone the best of ourselves, and everyone we encounter is deserving of dignity. That applies to every human being on this planet. I would argue these are among the most important obligations we have. From them, the world we need could emerge. Instead, many of us become like Pansy; so incoherently angry and afraid that we end up hurting the people we love most, and need most.

The hope in this film does not lie with Pansy; the final scene implies she may not be able to overcome her pain. The hope lies with her son, who tries to connect with others, even though he has never had a model for how to do so. But he tries. This is what Leigh seems to be saying: being alive is not easy—we have made it extraordinarily difficult. Still, the most important part of life is to reach out, to connect, and to try to understand others. Maybe we get hurt. Maybe we make a friend. To do this is to live.

One thought on “Movie Review – Hard Truths”