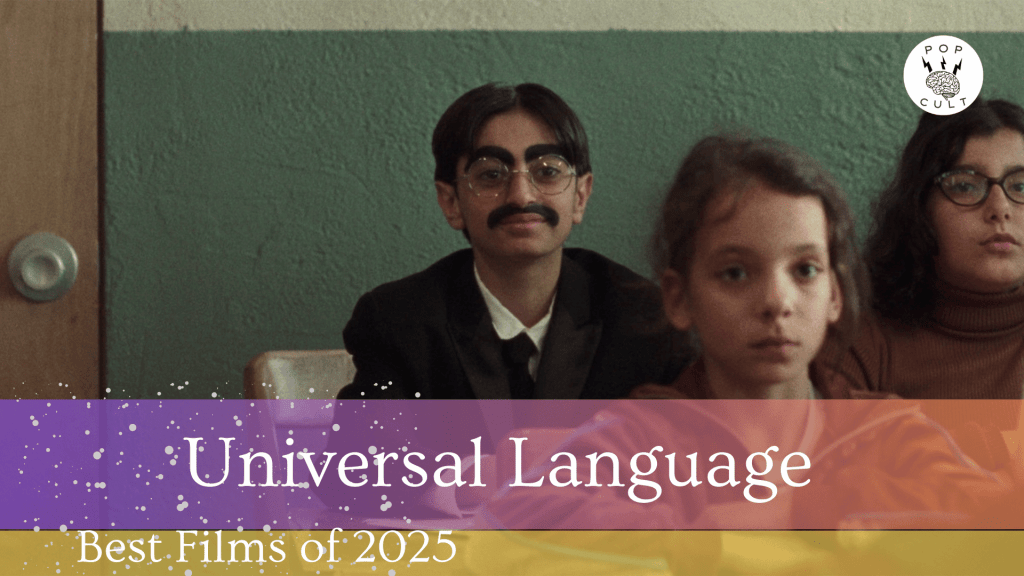

Universal Language (2025)

Written by Ila Firouzabadi, Pirouz Nemati, and Matthew Rankin

Directed by Matthew Rankin

Universal Language is a hard film to pin down. It has the framing and subtle sense of humor of Wes Anderson, yet it is also informed by filmmaker Matthew Rankin’s love of Iranian cinema, which he discovered as a young man in Winnipeg. That’s the other key element: Rankin’s own feelings about his hometown, a landscape of brutalist architecture and perpetual snowbanks. The languages spoken by the cast are Farsi and French, and almost every cast member is Iranian. If this sounds like an odd mix, you would be right. The humor is offbeat and the world is very strange, while still grounded in authentic emotions, culminating in an ending that will linger with you.

Universal Language unfolds across several loosely connected storylines in which everyday life operates according to baffling but rigid rules. The film follows a schoolgirl determined to recover a banknote frozen in ice, a government worker tasked with enforcing opaque regulations, and a tour guide who leads visitors through sites of quiet, existential disappointment—all moving through the same snowbound city without ever quite intersecting. As these vignettes accumulate, they reveal a world governed by misplaced logic and emotional deadpan, where language conflicts with understanding and civic systems function without much thought. Plot, in the conventional sense, is secondary; the film progresses instead through coincidence and absurd detours, gradually forming a portrait of alienation and cultural dislocation.

This is probably one of the most unpredictable films I’ve seen in a while, yet when characters cross paths or serendipity intervenes, it still makes sense. I’d go as far as to say this is a film poem, with little interest in traditional plot. It’s similar in many ways to the films of Tyler Taormina (Ham on Rye, Happer’s Comet), which are vibes-based rather than focused on hitting plot beats. By employing non-linear elements, Rankin is able to step back and show us how a background character came to be in their situation when another character encounters them later. The flow is impeccable, moving us from one person to the next as we explore this fascinating blend of Winnipeg and Tehran.

This version of Winnipeg is stuck in an early-1980s aesthetic, evident in the clothing and interior design. The Iranian elements emerge in the way places like Tim Hortons are reimagined into Middle Eastern versions of themselves. Then there are the simply odd choices, like a cemetery located on a grassy median surrounded by traffic-congested highways. Characters have bizarre obsessions; there’s one subplot in which characters get caught up in a contest involving turkeys. The picture is shot on Super 16 film, which helps enhance the period look, along with costumes and hairstyles that seem lifted straight from a Sears catalog.

Amid this cacophony of strangeness is a deeply human story. Matthew is making his way home because his mother is gravely ill. Paralleling this is the day-to-day routine of tour guide Massoud, whose stops consist of the most mundane locations imaginable. A surprising reveal in the final act forces us to reevaluate what initially seemed like a series of disconnected episodes unfolding within the same imagined reality. What emerges is a very personal story for Rankin about identity and his hometown. It was this sudden realization that cemented Universal Language as one of the best films I saw all year.

One thought on “Movie Review – Universal Language”