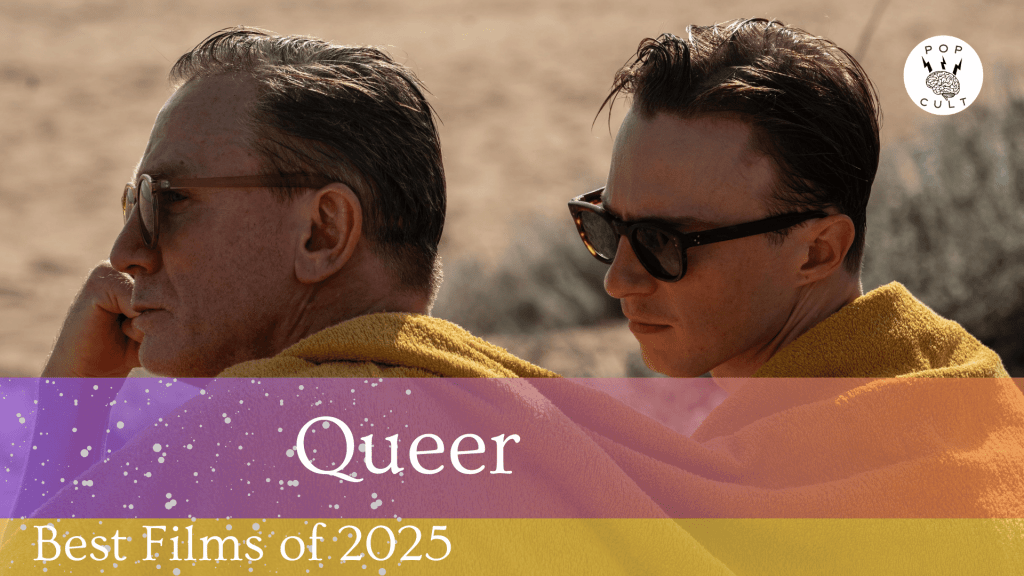

Queer (2024)

Written by Justin Kuritzkes

Directed by Luca Guadagnino

Luca Guadagnino has been on quite the streak lately. In the last three years alone he’s made Bones and All, Challengers, After the Hunt and this film. While he’s not been to everyone’s taste, I think everything he makes is worth a view and showcases his filmmaking prowess whether on a technical or artistic level or both. Guadagnino resists the temptation to dramatize desire into a standard plot and instead lets longing exist as visual aesthetics. The film treats obsession not as pathology or romance, but as a state of being. It is disorienting, humiliating, sometimes tender, often unbearable. This is a film you feel and if you feel it, the characters and their experiences will linger with you for a long time.

Queer follows William Lee (Daniel Craig), an American expatriate drifting through Mexico City in the early 1950s. He numbs himself with alcohol and casual encounters while quietly unraveling. His life shifts when he becomes fixated on Eugene Allerton (Drew Starkey), a younger former U.S. serviceman whose emotional distance only deepens Lee’s obsession. Lee projects fantasies of intimacy and meaning onto a relationship that remains fundamentally asymmetrical. Their connection eventually carries them out of the city and into a hallucinatory journey through South America. Lee’s longing and addiction intensify, transforming his obsession into self-destruction. The film traces this spiral not toward resolution, but toward a deeper exposure of the quiet self-inflicted violence of wanting someone who will never fully want you back.

Guadagnino makes a series of deliberate stylistic choices that keep the viewer slightly off balance, mirroring William Lee’s own sense of displacement. The lighting is conspicuously artificial with flattened interiors and overlit night spaces that feel constructed rather than lived in. Instead of disappearing into historical authenticity, the film continually signals itself as a contemporary interpretation of the past, a period piece that knows it is one. This stylistic dislocation creates environments that feel unreal, as though Lee is moving through sets or his memory rather than spaces he truly inhabits. The effect is psychological. We are never allowed to forget his estrangement from others, and from himself. Guadagnino turns artifice into a theme, externalizing Lee’s inability to anchor his desires.

The bursts of surreal imagery feel like direct inheritances from William S. Burroughs’s work, the stream of consciousness style of the Beatniks. Guadagnino embraces this elasticity, allowing erotic fantasy and dream logic to intrude on the film’s surface. In doing so, the film actively pushes back against puritanical Western traditions that demand restraint around queer desire. Instead, it revels in it; queer eroticism is sometimes intense and never apologetic. Sex and longing are treated as experiential truths felt in the way reality becomes so distorted around Lee. The result is cinema that treats queerness not as subtext or metaphor, but as a destabilizing, sensual force that reshapes reality itself and wounds when it goes unfulfilled.

It becomes obvious early on in the film that Lee’s desire for Allerton is going to go unfulfilled. But that is what makes for so many romantic tragedies. The audience has an awareness because we aren’t fully caught up in the bliss of believing things will turn out alright. We notice Allerton’s body language and responses more than Lee who is allowing himself to ignore all of it. He can’t give up on the dream because then it would have to acknowledge the despairing situation he is in. It’s also no coincidence that Allerton resembles Lee so closely, our main character is falling in love with a younger version of himself who he will never actually get to have. This is emphasized in the gorgeous images where Lee and Allerton become like transparent phantoms, trying but unable to get in sync with each other.

Craig’s performance lives in a fascinating contradiction: he visibly carries age in his posture and fatigue, yet still radiates the residual gravity of a movie star. It recalls the late-career melancholy of someone like William Holden. Craig sustains a constant tension between nervous self-awareness and lingering confidence, and it’s that friction that drives Lee to keep humiliating himself in small, accumulating ways as his infatuation with Allerton deepens. He plays Lee as a man whose life has become a performance; he’s witty, articulate, socially fluent, yet one that no longer convinces even its actor. Beneath the eloquence is a quiet mourning for the person Lee imagined he might become, a loss made painfully visible in Allerton, who seems to embody youth, possibility, and emotional distance all at once. Craig makes Lee’s tragedy inseparable from his intelligence: he understands the shape of his own failure, but not its depth, and that blindness gives the performance its ache.

The film is over the top in the same way nearly all of Luca Guadagnino’s work is; which is to say that excess isn’t a flaw so much as the operating principle. He’s never offered comfort or clarity, only the promise that you will feel something sharply, maybe even resentfully. It feels intentional, almost mischievous and one you rarely see anymore from films carrying recognizable stars. His movies gleam like luxury advertisements but thrum with something dirtier underneath, a kind of gutter poetry. The meaning isn’t hidden in symbols or speeches; it’s embedded in gesture, rhythm, and drift. The motion is the message.

One thought on “Movie Review – Queer”