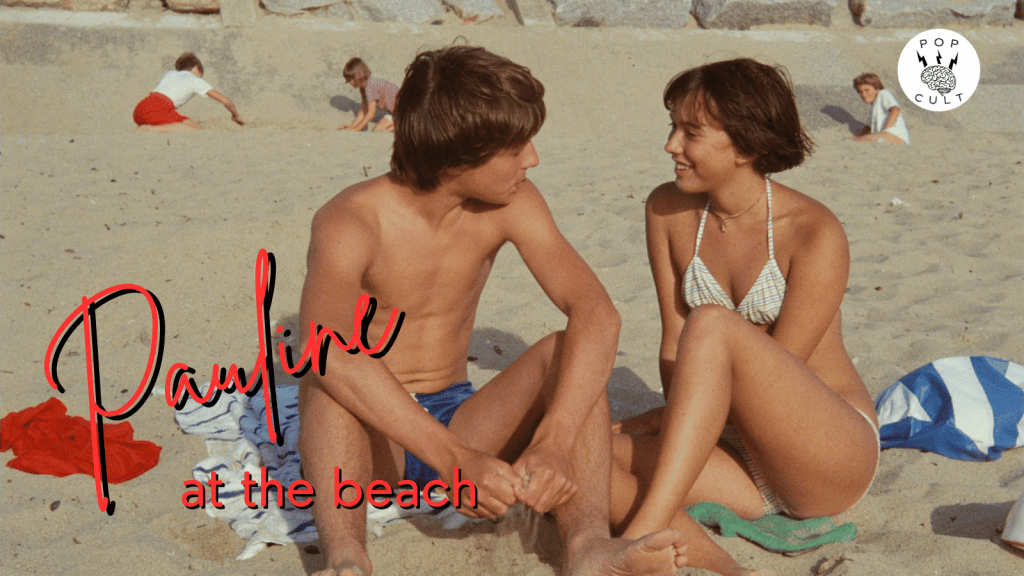

Pauline at the Beach (1983)

Written & Directed by Eric Rohmer,

Eric Rohmer was the right age to join his colleagues from the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema in becoming a filmmaker. Jean Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, whom he worked alongside as editor of the magazine, became the two most prominent names associated with the French New Wave. He did make movies, but not at the same breakneck pace as the others, and he didn’t receive the same level of acclaim until much later in his career. The filmmaker was very secretive about his private life, including that Eric Rohmer wasn’t his real name but a combination of actor/director Erich von Stroheim and writer Sax Rohmer. Unlike his colleagues, Rohmer outlasted them in terms of career length, finding his most significant acclaim in the 1970s & 80s. It was in the 1980s that he began a thematic series titled “Comedies and Proverbs,” with each film based on common sayings in French culture. One of these was Pauline at the Beach.

Pauline (Amanda Langlet) has gone to the north-western coast of France to hang out with her adult cousin Marion (Arielle Dombasle) for part of the summer vacation. The most frequent topic of conversation is centered around love & sex, with Pauline being 15 years old and confessing she has never experienced either in any authentic, passionate way. On the beach the next day, Marion spots a past lover, Pierre (Pascal Gregory), surfing. They strike up a flirtatious conversation that is broken up with the arrival of Henri (Féodor Atkine). Henri is clearly into Marion and has more wealth than Pierre.

He invites everyone back to his place, where he proceeds to steal Marion’s attention away. Eventually, Marion chooses Henri and begins to ignore Pierre, claiming his jealous nature is a turn-off. Pauline also finds someone, Sylvain, and they start spending more and more time together, including using Henri’s bedroom while he is away. Eventually, a moment of infidelity occurs in one couple, compounded by lies upon lies. By the end of the summer, Pauline has learned a harsh lesson about how people tend to make things worse rather than being honest.

The core theme of Pauline at the Beach is how we invent stories to keep living. In Marion’s case, she is confronted with contrasting facts about something that happened while she was away for a day. One narrative is a ludicrous yet less harsh version of events, while the other is an extremely painful set of facts to embrace. This is also shown in the big proclamations about their philosophical beliefs on love. For many of the adults, they want to say that love is this majestic, beautiful experience. However, they quickly betray these boldly expressed beliefs when presented with specific opportunities. It seems the chance at quick sex is more important than the ideals of love.

Rohmer is doing this on purpose, wanting to show how the things we often speak aloud when trying to establish ourselves as virtuous & ethical are often paper thin. Humans are constantly primal in their behaviors, and rather than being honest about our nature as animals, we want to join in the collective idea that we are potentially creatures of rock-solid morals. Our way of justifying this psychologically crippling contradiction is to invent stories to tell ourselves that soften the blows. The purpose of Pauline’s inclusion becomes apparent near the film’s end when she becomes a voice of ideas the adults haven’t raised. The film shows us that she is no longer coming from the mindset of a little child, but she also isn’t an adult wholly wrapped up in decades of carefully constructed self-delusion. She sees the relations between the adults in a way they will never allow themselves to accept.

Pauline at the Beach is a highly talky film; little happens beyond conversations. Yet, I never felt that it was dragging on. These conversations are a treat to listen to, with each pairing of characters adding to the larger dialogue around the themes. In a certain way, the exchanges draw “battle lines”; characters have their point of view set up so that later when the big conflict occurs, everything flows like a line of dominoes. It makes sense that this person is at odds with that because of what we learned in an earlier conversation.

The camera isn’t completely static, but it doesn’t do much moving. Add Rohmer’s strong sense of blocking, and each scene feels like a framed photo. Just enough of the setting is ever-present, the lighting is never too harsh or insufficient, and from start to finish, the feeling of a vacation getaway to the beach emanates from the screen. Rohmer isn’t going for a tone that presents anything as earth-shattering as Marion, probably the most wronged party in the film, won’t allow herself to absorb the weight of the betrayal. The film doesn’t take a dark turn and allows things to remain feeling light & airy.

Like Mike Nichols’ The Graduate, Pauline at the Beach is the story of a young person getting a full view of what life is like as an adult, particularly when it comes to love & sex. The film never tells us what Pauline decides about her life; she certainly has much to think about after this summer. The teenager thought she understood what people meant when they talked about love, but now that feels far more murky & unsure. Pauline sees how vulnerability with another can leave a person bruised & hurting. Will she be more reticent in pursuing her crushes in the future after witnessing all of this? We don’t really know, as intended. The audience is meant to leave asking themselves whose perspective they identify with most: the naive teenage girl who came to understand love as far more complex than she first imagined or the adults who live in denial of this complexity, preferring lies & fantasies as a balm for the pain.

One thought on “Movie Review – Pauline at the Beach”