Juvenile Court (1973)

Directed by Frederick Wiseman

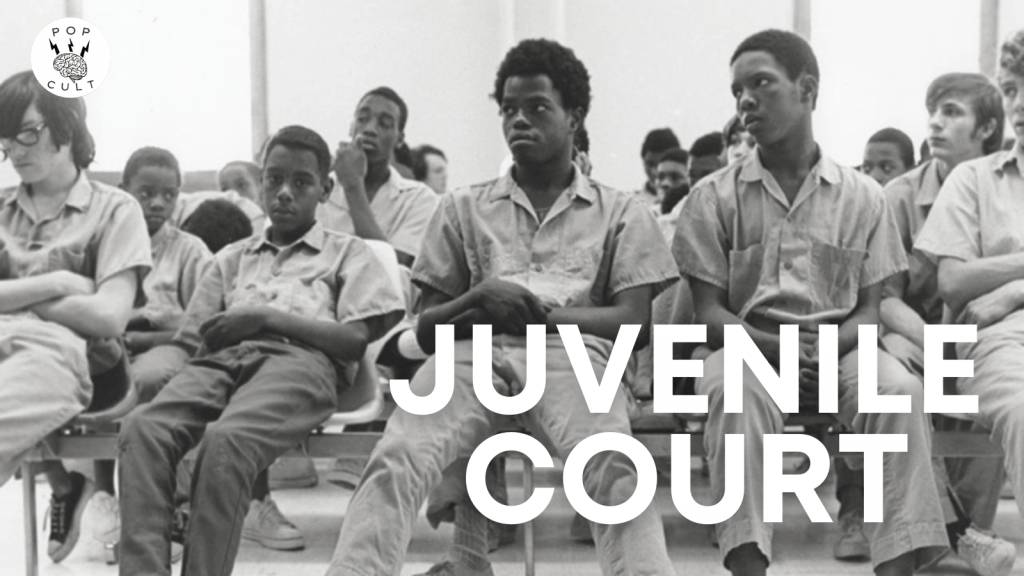

Frederick Wiseman’s seventh film, Juvenile Court, came after producing at least one documentary a year from 1968. High School & Law and Order each contemplated how American institutions subjected people to forms of control. The former sees how we teach children as wrapped up in authoritarian ends, while the latter is about how authoritarianism is exercised in the community. It makes sense that Wiseman would make Juvenile Court as it is where these two paths converge, the place where young people are brutally institutionalized to “get them in line.” In a film that foresees Wiseman’s magnum opus, Welfare, he constructs tighter narratives, following a small number of young people and families through the court process.

I begin with the end. Robert Singleton is weeks shy of his eighteenth birthday. He is accused of two counts of armed robbery and attends a hearing at the Juvenile Court of Shelby County, Tennessee. The purpose of the hearing is to determine one thing: should Robert be tried as a juvenile or an adult. The potential sentence of being tried as an adult carries a heavy prison sentence. Robert insists that he was only the driver and that his adult “accomplice” threatened to kill him if he drove away. Robert never entered either of the two establishments the adult robbed. The D.A. has requested that the trial be moved to the criminal court. Robert’s lawyer passionately argues that nothing in the law says that if a defendant is “close to the age of majority,” they can be tried as adults.

Judge Kenneth Turner listens to the arguments of both sides in his quarters and has to keep reminding Robert’s lawyer that this is not to determine guilt or innocence but which venue the trial will be held in. That doesn’t make the young man’s plight less harrowing now. The way this judge rules will have an effect so dramatic on Robert’s life that it feels like it should be illegal to do such a thing to another human being. Yet, for a moment so weighted down with import, the way the lawyers and judge speak feels almost casual, relaxed. But that’s part of the performance of justice, isn’t it? The feigned decorum hides the roiling brutality just underneath the surface.

The wrinkle in the whole affair is that Robert wants this to go to trial because he’s insistent on proving his innocence. His lawyer keeps arguing that accepting a plea in the juvenile court will mean the young man will be sent to State Vocational Training School in rural Pikeville indefinitely. Pushing for a trial means trying him with a minimum 20-year sentence as an adult. Robert’s lawyer and Judge Turner plead with him in court to understand that Pikeville is the best option for him in this scenario.

“Is there any justice? Is there any justice for me?” Robert tearfully sobs in court. You watch as something inside him gives way to the understanding that there is no hope for someone born near the bottom of the ladder. There will never be justice for Robert. He will be shipped off to Pikeville. Very likely sexually assaulted and physically brutalized. When the people in charge decide he can be released, Robert will be a person who is much more disconnected from the cruel world in which they are expected to survive.

Wiseman spent two months in the Shelby County juvenile court’s halls, offices, and courtrooms. He edited this documentary with a level of precise craft that reveals a great storyteller. These people, these children, come to feel like richly nuanced characters in a fictional narrative, which serves to remind us everyone around us is like this. We just aren’t there to see (or we choose to ignore those moments) when their humanity shines forth. Unlike the popular incel reactionary notion of people as NPCs, they are, in fact, full of life. One youth angles accepting Jesus into his heart as a means to avoid Pikeville when he’s put on trial for possession with intent to sell. That ends with an annoyed Turner and this court being remanded to criminal court.

The bleaker stories are the ones where a young 11-year-old Black girl is being placed in state custody. She is chronically running away from home, and the conversation alludes to her doing sex work. It seems absurd as she is such a little child. The white woman court employee admonishes the girl to “Stop your crying.” The voice is soft & nurturing, yet the words tell the girl to deny her reasonable emotions.

Then there’s the teenage boy being psychologically evaluated to determine if the accusations he sexually molested a child he was babysitting are true. We hear the boy defend himself. We see the mother meeting with the judge to discuss her thoughts. The film doesn’t allow us an easy path to know what actually happened. Wiseman just presents what people say and the decisions of the court. Beyond his choice of what to show and cut, what you feel about this film comes from you.

The core thesis of the court appears to be that a youth’s acceptance of their guilt will “free” them, but their insistence on innocence is worthy of a greater punishment. It is never seen as a possibility that the young person would be innocent of the crime. Why? Because the police arrested them and they have been charged. In a society where the authority of the police is nigh unquestionable, then a child is only being impertinent if they won’t admit their guilt. While this was made over fifty years ago, little has changed beyond some cosmetics and slight structural shifts. Wiseman was about to make his most remarkable work, which we will discuss next time – Welfare.

2 thoughts on “Movie Review – Juvenile Court”