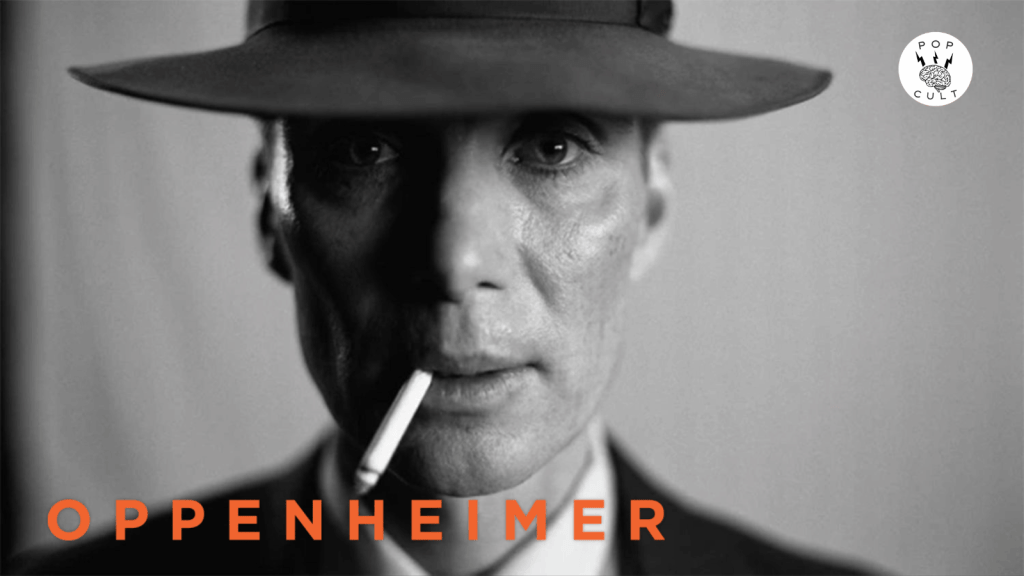

Oppenheimer (2023)

Written and directed by Christopher Nolan

Western culture is obsessed with singular individuals. Any brief survey of historical events reveals that while there may be people in positions of leadership or authority, they rarely act alone. The Nazis were not simply Hitler. Many of them passed through the war untarnished and even got cushy jobs working for the United States government, like Werner Von Braun. A general depends upon an army. The U.S. government is not just the President. Oppenheimer was placed in a leadership position at Los Alamos, but the construction and deployment of the atomic bomb cannot be placed at his feet alone. That also doesn’t excuse his involvement, either.

Based on the biography American Prometheus, the film follows physicist Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) in a non-linear structure focusing on his years as a doctoral student, his work at Los Alamos developing the atomic bomb, and the aftermath where he is put at odds with atomic energy bureaucrat Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey, Jr.). The film jumps the audience back and forth in time, finding thematic parallels between moments in Oppenheimer’s life. A conversation he has with Albert Einstein just before the significant work of Oppenheimer’s career began serves as a final note that adds a dark recontextualization of everything that came after.

I have seen complaints about this film being historically inaccurate. These complaints are odd as they imply that the people issuing them believe that movies based on historical events are typically accurate reportings of their subjects. There is no narrative film that is an accurate account of what actually happened to the person featured. I wouldn’t say Oppenheimer is a hagiography of its subject, either. If you want more factual tellings, I recommend seeking out a documentary or book.

Narrative films are always more reflective of the person making them than the bits of history they relate to. Gangs of New York is based on actual events, but it is more of a film about Scorsese exploring his relationship with the city than it is a rigid point-by-point detailing of history. The problem with Western audiences, particularly American ones, is that propaganda is so ubiquitous and presented as factually accurate. This is what a society where media illiteracy is made the norm looks like. Where Trump talks about Hannibal Lecter like he’s a real person. Or someone thinks details about Barbie’s creator in that film were anything but corporate bullshit.

By the end of this film, I didn’t feel like I was expected to look up to Oppenheimer. The movie criticizes his sudden vocalizing of his problems with the weaponization of atomic energy as “too little, too late.” Multiple characters call him out, asking why, if he holds this belief so firmly, didn’t he say something earlier? I knew I wouldn’t get something profound as it’s a Hollywood movie, but I was surprised with where it ends. Anyone coming out of this thinking Oppenheimer was a hero needs to really work on their literacy. Oppenheimer was a person at the end of the day, and we are just as capable of going along with the system we live within. In fact, we do that every day of our lives unless you are someone with a tremendous amount of integrity and strength.

I wasn’t sure what to make of the Jean Tatlock subplot. I understood how it fit into the narrative, but I don’t think casting Florence Pugh in such a small and ultimately insignificant role made much sense. There didn’t seem to be a lot on the page for her to work with, and because Pugh is such a well-known actress at this point, it was more distracting than anything else. Tatlock would have been a fantastic role to cast an unknown actress in. A supporting part that could have helped shine the spotlight on someone new and launch a career. But because this is Hollywood, and we have to make it an “all-star” cast, I guess you cannot do that.

The first half of the picture was its weakest. There was so much exposition, and the dialogue was the worst part. Everyone is over-explaining who they are and what they are doing. Nolan is a very skilled filmmaker, but when it comes to making me care about the characters, he’s just not been that great, in my opinion. I never teared up watching Interstellar because I felt Nolan was too up his own butt with that picture. That’s not to say he isn’t with this one, but the second half seems to be able to lean back on the emotional elements of the story and stop exposition dumping.

Similar things are happening in Oppenheimer in the same way that The Killer was David Fincher’s reflection on himself as a filmmaker. Nolan has always been fascinated with the gulf between the individual and the system they exist within, especially as a director who, it could be argued, jump-started the superhero/IP nightmare we are currently living through. The Dark Knight infamously gives us the cellphone moment, where mass surveillance is justified to protect the system. Then, The Dark Knight Rises has a character sacrificing themselves for the greater good, literally atomizing themselves. One thing we must make peace with is that figures like Robert Oppenheimer will always be unknowable to us. Everything we read or watch about them is an attempt at guessing who they were. Nolan conveys this exceptionally well through the complex visual sequences meant to represent our protagonist’s obsessive focus on the molecular nature of existence.

What Oppenheimer represents is a highly ambitious, intricately constructed 21st-century film. Nothing about this feels like it could have been made before our moment. How Nolan constructs his images and how they are edited non-linearly and connected through themes is awe-inspiring. Ludwig Göransson’s score is a masterpiece and acted as emotional propulsion throughout the movie, and I think it helped me not to feel the runtime. I understand these critiques of the film as feeling like a three-hour trailer, but I think that is why it doesn’t feel so long. Of all the cast, Robert Downey Jr. is a standout. He’s the only person on screen who feels natural in every scene he appears in, and I forgot it was him.

My favorite thing was the structure. This storytelling framework could be applied to something else, particularly something non-historical, and would result in a compelling film. Nolan has always liked to play with time & perspective (see The Prestige and Tenet), and he successfully employs that here. I get it if you don’t like it, but I’ve always enjoyed a well-told narrative that plays with time, so this was a treat for me. I’d like to see another director use this framework just to see the result.

But this is a series about the atomic bombing of Japan, so we need to relate it back to this theme. I never felt the film let Oppenheimer off. Like nearly every Hollywood film about the atomic bomb, it refuses to show the results. We are kept at a distance with that moment represented by an address Oppenheimer gives the staff at Los Alamos about the bomb’s deployment. Nolan frames this as a panic attack from the scientist’s perspective, which does feel like skirting the true impact seeing a recreation of the bombing would have delivered. However, the movie is called Oppenheimer, and I can also see the argument for keeping the camera firmly focused on the subject. If you feel disgusted during that scene, I would argue that was the intent.

I think the film brings up (but doesn’t adequately explore) the danger of science being made a tool of imperialism. The atomic bomb was not the first instance of this. Racial science has been one of the most infamous, an attempt to use Western scientific ideals to justify the enslavement and dehumanization of our fellow human beings. The ease with which so many people accept the bombing of Japan is an extension of this. They have psychologically justified their white superiority so the deaths of Japanese people they don’t have to see on the other side of the world are as real to them as a fairy tale.

I think the film’s final line did get across one of the main theses of the picture – being capable of developing a technology doesn’t mean that we should; we may not be morally & intellectually evolved enough to handle it. For a Hollywood movie, it was more critical than I expected, with my expectation being that it would try to make Oppenheimer a heroic figure. He is not. That final line secures that fact. The world did not begin its descent with the dropping of atomic bombs, but it was far earlier when humans worked up justifications of how to not see each other as humans. If you genuinely see humanity in another, it makes war an impossibility.

I agree that the film was about science being a tool of imperialism and how scientists can fall into that trap.