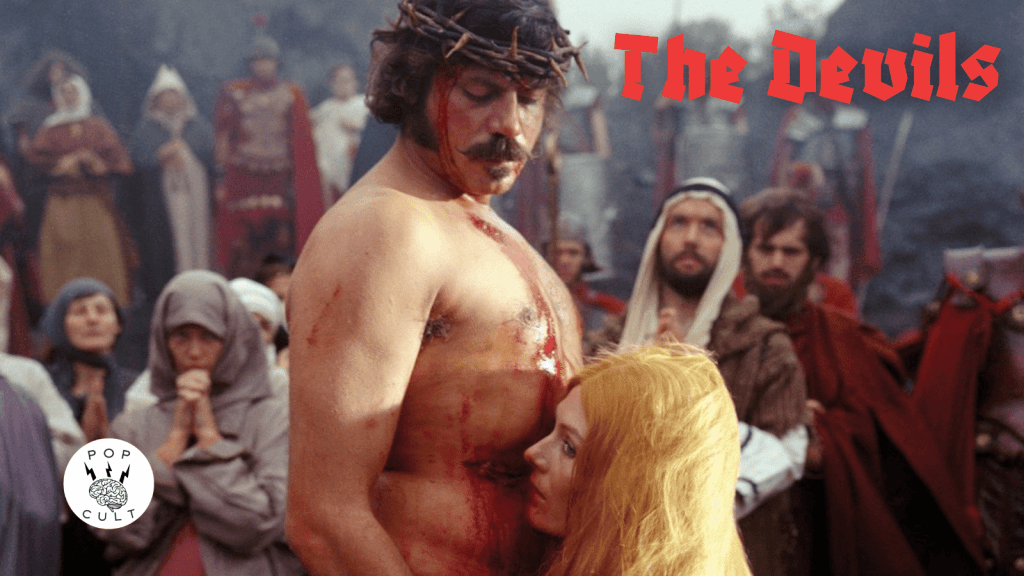

The Devils (1971)

Written and directed by Ken Russell

They don’t make movies like this anymore, but I wish they did. The Devils was a Warner Brothers production based on the stage play of the same name, which in turn was based on the Aldous Huxley novel The Devils of Loudon. 1971 was a very fruitful year for director Ken Russell. This was released alongside The Music Lovers, a Tchaikovsky biopic, and The Boy Friend, a 1920s period musical starring Twiggy. These weren’t his first films, but they did come after his picture Women In Love garnered Russell Golden Globes and Oscars nods. In classic Ken Russell fashion, The Devils is not adhering closely to the tropes associated with the genre – in this instance, historical drama. It is a wild experience, visceral and hallucinatory, aided by the production design of the great Derek Jarman.

In 17th-century France, the country licked its wounds after a series of religious conflicts. The tyrant Cardinal Richelieu seeks to influence King Louis XIII that the remaining Protestants must be driven out, and the best way to do that is to destroy the fortified walls of the cities that were built during the wars. However, the King promised Loudon’s governor that his city would be spared. The Cardinal won’t let that slip by and finds a willing aide in Sister Jeanne de Agnes (Vanessa Redgrave).

The governor has died, and now Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), a charismatic priest, has assumed control. Sister Jeanne, full of neuroses about her physical disability, oversees the local Ursine convent and spends much of her time obsessing over Grandier, having intense sexual fantasies about him. Grandier is entirely unaware of this and carries on an affair with a fellow priest’s niece, whom he impregnates. When she tells him the news he dismisses her as a priest can’t have a child, only to hook up with Madeline. Sister Jeanne figures this out and goes on to accuse her fantasy lover of performing witchcraft on her and the other nuns. Thus, an inquisition must begin.

When you look at Warner Bros today, now Warner Discovery, I see a timid, frightened movie studio that used to take on new artists and bold films. Now, they are a cluster of shaking finance bros making poor-quality films and shelving whatever they can for a tax write-off. Watching The Devils is to be transported to a time when studios still loved making money, but at least some people greenlighting pictures had room to put strange, challenging work on the screens of cineplexes. There are no easily loveable protagonists or easily hateable antagonists. We see a landscape still trapped in the mystification of the ancient world and driven mad by the Black Plague, which ignores their religious platitudes.

Sister Jeanne is a character I assume most audience members will have a strong opinion on. Redgrave is downright fearless in her performance. She’s a mother superior who is completely insane, but who do we meet here that isn’t. She has a hunched back with the bones of her spinal column pushing against the skin. When Madeline inquires about what kind of women become nuns, Jeanne replies with vicious delight that the women here are those whose parents couldn’t marry them off – the deformed and the ones who wouldn’t follow the rules. Yet, she’s no radical; Jeanne is insipidly petty, happily tearing apart Grandier for not noticing her and then suddenly regretting it when it’s too late. Her purpose, she realizes in the third act, was to help the Cardinal justify the execution of Grandier so he could establish his dominance of France.

The world of The Devils is one of conflict pushed to its highest levels between debauchery and the Church. The type of Catholicism that existed at this time is far closer to the paganism it eclipsed than the spiritually devoid pedophilia factory it has become today. That doesn’t mean it was better. I have no doubt those sex abuses were occurring back then. The people’s connection to the old ways in Europe had not been quite so severed yet. Thus, the clergy found they only had to appeal to the people’s passions and desires rather than to any sort of intellect. Father Barre is a perfect example of this, how the film, with nuance, combines the aesthetics of the 1960s counterculture with these long-haired religious figures who simply need to get the crowd worked up to “prove their point.”

What Russell manages to pull off here is an explosion of chaos that the film builds towards. When the nuns become caught up in Sister Jeanne’s claims, they rip off their clothes and begin cavorting naked in the convent and around the city. We discover that beneath many of their habits are heads shaved clean or as close to the scalp as possible. They perform sex acts solo and with each other in front of the people. It begins to become clear that Jeanne’s lies serve as a pressure release valve for these young women forced into the servitude of the Church. They have found a way to give in to their desires and absolve themselves of all guilt. The Devil, in league with Grandier, made them do it.

It is this sudden sexual freedom that signals the need for the Cardinal and then the King to get involved. This is chaos, and how can one of France’s cities be allowed to descend into such madness? And wouldn’t you know, the man standing in the way of those walls being torn down is responsible for it. The modernist style combined with a 17th-century French setting puts us in an even more surreal dream state. Is this the real world or just a dream? I think that it’s essential to understand the mind of your average European at the time who believed that the world was influenced by spirits, gods, and devils. The world was a surreal, haunted place for those people all the time.

Russell’s camera matches the frenetic energy that breaks loose with the nuns. Whip pans swing our attention from one event to the next. High-angle shots denote one character’s power over another, or the reverse showcases a person’s fealty. The composition and blocking of scenes were clearly something a lot of time was put into, and it paid off on screen. This is pre-digitally inserting crowds, so the masses of people that Russell and crew coordinated and choreographed are all the more impressive. The tone and style of this film reminded me at times of Tom Twyker’s Perfume, another darkly surreal movie about France.

All the more fascinating is that Russell was on record when he said he was raised Catholic and still held his faith as an important part of his life. But he is a person of faith who truly understands his upbringing. There is a difference between the beliefs and the institutions. The more humans try to formalize and narrow spirituality, the greater they ruin it. Russell sees this and shows it through the intermingling of state and religious power, both with agendas and more than happy to use the other to get closer to their goals. It’s one thing for you or me to be a believer, but when the leaders of a nation use religion as justification for their crimes, it is another thing entirely; it is the definition of blasphemy.

The Devils is one of the all-time greats. I knew that as soon as the end credits started rolling, I sat here wholly stunned at the masterpiece I’d witnessed. It’s fairly common to see a director bite off more than they can chew, trying to make a dozen states about unwieldy things in a single movie. I think Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales is a great example of that. If only those filmmakers would pay close attention to what Ken Russell did here. He can say everything he wants by being smart and economical and knowing when to go big versus pulling back. I don’t think the horrors & dangers of religious mania have ever been better captured.

3 thoughts on “Movie Review – The Devils”