This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (2019)

Written and directed by Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese

Just last week, I saw a clip from a Fox News program where they were discussing recent cuts to USAID programs. At one point, Jesse Watters mispronounced Lesotho’s name and immediately commented that no one knew where it was. It was met with sophomoric chuckles from his cronies. Ironically, I watched this film just a few days ago. Lesotho was one of a handful of African nations I could locate on the map. That’s because it’s geographically unique in that it sits inside the country of South Africa.

Lesotho is a sovereign conclave with the nickname The Kingdom of the Sky. This is because it is located in the Maloti Mountains, which contain Thabana Ntlenyana, the highest point in Southern Africa. For most of its history, the area was home to the nomadic San people. During the warm Medieval period, it began to attract more communities because of its fertile soil. This ethnic group became known as the Basotho and dealt with several incursions, including from the Zulu and eventually European colonists.

The kingdom was formally declared in 1824 after a war, but there was an ongoing power struggle with the Cape Colony. In the early 1990s, the kingdom began transitioning to constitutional democracy. What followed has been a roller coaster of stability and revolt. When this film was made, Prime Minister Thomas Thabane suspended parliament and attempted to remove a top general. Eventually, he fled Lesotho and formally stepped down after accusations he was involved in the murder of his ex-wife. Needless to say, this film was made amid a chaotic time.

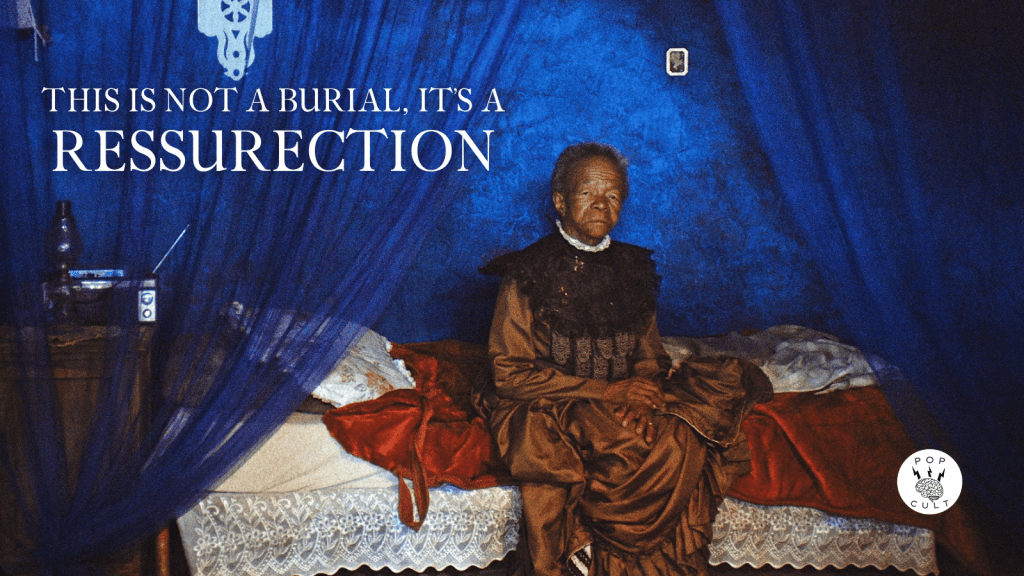

The film opens with 80-year-old Mantoa (Mary Twahala) grieving as she is the last of her family left alive. She comes to the conclusion that she wants to prepare her own funeral as she is done with life and ready to embrace death. At the same time, her community is being uprooted as the drought in South Africa has led to the construction of a new dam in the mountains. This will cause Mantoa’s village to be flooded, which means all residents are displaced. This will also involve removing bodies from the community cemetery so they can be interred in another location.

Adding another absorbing layer to this narrative is that it is framed as a story being told by a lesiba player (Jerry Mofokeng Wa Makhetha) in a run-down tavern. The lesiba is a mouth-blown stringed instrument that creates a unique sound. The tavern is a rather bleak setting; the other patrons are bathed in shadows, and our musician tells us the story of Mantoa as if he were sharing a folktale.

The location where she lives is known as the Valley of Tears, a reference to both it becoming a water basin with the construction of the dam and the grief of its people at being removed from their homes. The narrator explains the village was renamed by missionaries in the 1830s to Nasaretha. He continues, “They say in Nasaretha, if you place your ear to the ground, you can still hear the cries and whispers of those who perished under the flood, their spirits hallowing from the deep.” Setting and character are going to be intertwined here.

It’s Not a Burial contains some stunning images. It’s a testament that budget is important, but adherence to technical elements can make a “cheap” film feel like an incredible production. I was reminded of poetic cinema, particularly Wong Kar Wai. The smoky tavern where the narrator plays looks like a set out of Happy Together or In the Mood For Love. The same care and beauty are present in the exterior shots of the mountains and the community nestled inside them. I’d have to say these highlands look a lot like images I’ve seen of Peru, and even Lesotho’s clothing is similar.

Mantoa’s grief is not just hers but a reflection of her community. The film opens with news of her son, her last living relative, having died in a gold mine in a collapse. The funeral is bathed in gorgeous colors as the community surrounds the old woman. The ancestors, those who have died before us, are seen as the direct connection between humanity and the Great Creator. Removing their bodies from the land of their birth is a highly upsetting act. The bureaucrats can explain it as much as they want, but it won’t make the experience feel any better. Because Mantoa was preparing for her death, she expected to be buried next to her kin. That won’t be happening now.

Mary Twalha’s performance is incredible. She was a South African actress who had been working since the late 1980s and had clearly honed her craft over the decades. This was her penultimate film, and I can see that the themes of death and looking back are something she was authentically feeling. Mantoa’s pain is palpable. She weeps and screams to the point that villagers show up thinking she’s been attacked. It expresses an existential pain that privileged people simply cannot understand.

Without knowing much about Lesotho, I could feel that this film captured what it means to be one of those people. This Is Not a Burial resonates with a truth about a place, about a people, that I rarely see in American films. The director fully embraces and loves this land, which we feel in the care he takes to shoot the picture. The lighting is perfect, and the colors are bold.

My favorite scene in the film leans into the fable-like nature of the framing device. Mantoa sits in her home. It has burned to the ground, so most of it is ashes. She sits on her bed. Slowly, a flock of sheep wanders into the frame and gathers around her. They seem to see her pain and stand quietly in the space. It’s such a striking image and one of many that makes this an incredible viewing experience.

One thought on “Movie Review – This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection”