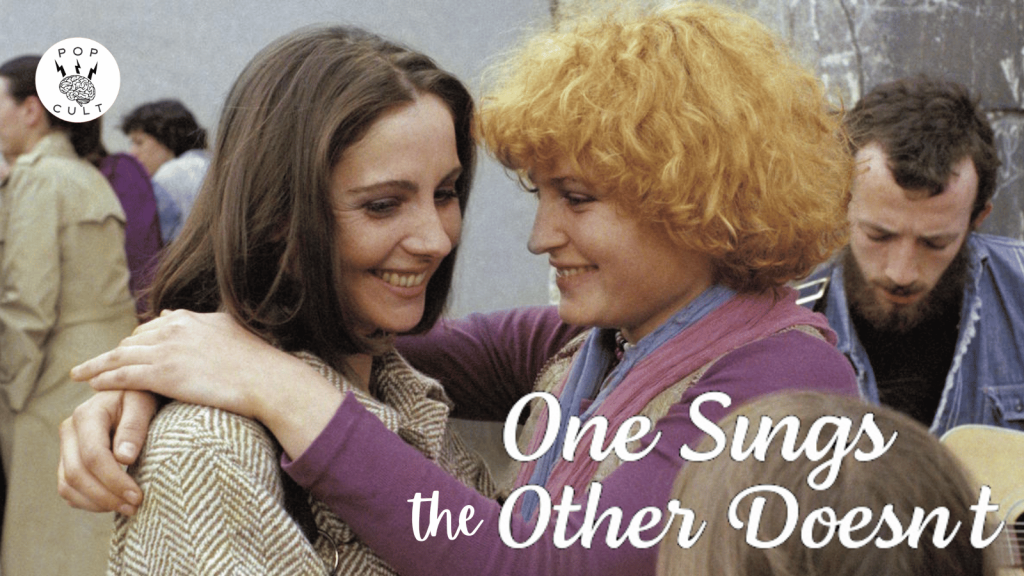

One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1976)

Written and directed by Agnes Varda

Time feels distorted. It didn’t just start with COVID-19 either. Our understanding of even recent history is blurred, with significant historical events from just a decade or two prior feeling like they happened so long ago or disconnected from our point in time. Part of this is the poor perception of the human brain, whose recall & memories have been proven very unreliable. It also emanates from the neoliberal project outlined in Francis Fukyama’s The End of History and The Last Man. The argument made via neoliberalism is that all possible political ideologies have been discovered & developed and that we live in a period in which no more historically significant events will happen. Essentially, human development is now a capitalist machine meant to run forever, powered by the “benevolence of capitalism.”

Yet, significant historical events have happened in our lifetimes and some in the years just before we were born. In the 1970s, director Agnes Varda signed the Manifesto of the 343, a petition created by French feminists declaring that they had illegal abortions. This manifesto was intended to push for the legalization of abortion in France for the same reason any people seek to legalize the procedure: it is a basic medical procedure that all childbearing people should have access to—a fundamental human right. By January 1975, the Veil Act passed, which repealed a penalty given to those who voluntarily choose to terminate a pregnancy.

One Sings, the Other Doesn’t is Agnes Varda’s story of two women who are friends during this time of social change, both dedicated to the cause of reproductive rights. Pauline was a 17-year-old high school student in 1962. She wanders into a photo gallery and recognizes the subject of one subject as her old neighbor Suzanne, with whom she had a friendship. The photographer is Suzanne’s current partner and helps the two reconnect. Suzanne is an older woman and, at 22, is pregnant for the third time. This is something that she cannot handle financially; the couple is stretched, and she wants to focus on the two children she is raising. Pauline lies to her parents about a school choir trip to get cash to help Suzanne travel to Switzerland to get the procedure.

Pauline’s parents find out and, in a rage, kick their only child out of the house. Pauline forms a band with other young women and lives a meager life traveling and performing. Suzanne is forced to move back in with her parents when an unexpected tragedy occurs. The film follows each woman over the next decade, watching them develop into new people and the intersection of their political growth in the women’s liberation movement. Pauline eventually has an abortion, knowing that she is not able to afford nor wants to raise a child. She even moves to Iran when she begins dating Darius, whom she eventually marries and starts a family with. The two women’s lives intersect again just as the fight for reproductive rights reaches its zenith. A large community forms around them as Varda delivers an uplifting, hopeful ending.

Varda showcases her commitment to taking character development seriously by not rushing through what, on the surface, feels like a straightforward narrative. What she does is emphasize the way people move in and out of each other’s lives. Sometimes, we stay connected even over long distances; sometimes, we lose sight of each other as life overtakes us. Those connections exist in various intensity levels, but they are always there in some form. For women, especially at this time, those connections were taking on another level of importance. They were part of a more significant political awakening, rejecting the chauvinism that had become so entrenched in everyday life.

The director is also putting her character writing on display here, able to quickly deliver paint strokes that define and help the audience understand who we are watching in just a few scenes. Pauline is a very defined person to us by the end of the first scene of the film. This means the rest of the picture takes those personality traits we saw on display, explores where they came from, and maps how they change as she grows. The same can be said for Suzanne, whose relationship with motherhood becomes a very complex journey. Varda’s daughter, Rosalie, plays Suzanne’s daughter at the film’s end. We see how Pauline & Suzanne’s friendship becomes a powerfully influential force on this young woman, helping her know what female friendship looks like and can be.

Varda’s time in Los Angeles, while her partner Jacques Demy wrote & directed Model Shop, afforded her contact with many different political activist movements of the time. She is on record as citing her time with the Black Panthers as having a profound influence on this enlightenment. This also pushed Varda into doing more documentary work, as we will see in upcoming reviews. It guided her on the next film we’ll review, where Varda collaborates with actress Sandrine Bonnaire in Vagabond.

2 thoughts on “Movie Review – One Sings, the Other Doesn’t”