Xala (1975)

Written and directed by Ousmane Sembène

In the mid-15th century, the Portuguese landed on the shores of Senegal and began a centuries-long occupation that included the British, the Dutch, and the French. It would not be until 1958 that Senegal declared its independence and merged with French Sudan to form the Mali Federation. That would not last long, and by 1960, they went back to their individual states. The process of decolonization is not quick & easy. When the colonizers withdraw, there is still tremendous work to do, a lot of which centers around removing the ideologies & ways of doing imposed on the colonized people by their occupiers. Ousmane Sembène is keenly aware of this, and in his film Xala, he produces an angry screed at how Western capitalism is allowed to fester in the systems of the post-colonial African people.

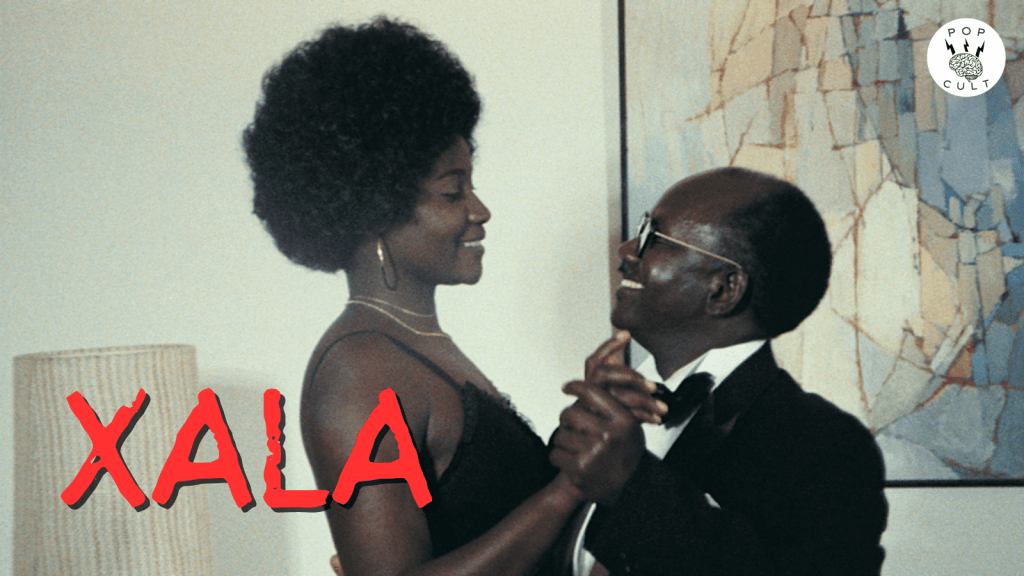

El Hadji Abdoukader Beye is a Senegalese businessman about to marry his third wife. This isn’t because he loves her; instead, by taking on a third wife in this polygamist society, he will be demonstrating his social and economic success. The wedding night comes, his new bridge is in bed, and…he can’t get it up. Beye suspects that one of his other two wives has cast a spell on him out of jealousy. This begins an odyssey to reverse the incantation, and he seeks the help of indigenous shamans. He becomes so consumed with this problem that he cannot see how his home and business are falling apart around him until it’s too late.

The opening sequence of Xala does an excellent job of communicating Sembène’s thesis. The newly elected Black leaders of Senegal arrive at the capitol, forcing the white colonizers out. These Black men take the seats at this table. Shortly after this the white men return with attache cases. The Black leaders open them and find stacks of cash – bribe money. They are happy with this, and with that money exchange, the old order has restored itself under this “new” regime. Much like Sembène’s Mandabi, he’s commenting that you cannot accept financial aid from entities that aim to exploit your people and community.

Of all Sembène’s films, I find Xala the most overtly enraged. It is undeniable that the filmmaker is incensed watching the leadership of his country go about repeating the same mistakes and accept help from the society that put them in this position in the first place. Beye’s illustrious business is selling rice on the black market; in his capacity as a community leader, Beye is responsible for the prices that cause a food staple to have to be sold like this.

Ironically, you can see the European influence in Sembène’s work. In his earlier work, he draws from the French New Wave, but by this period, and especially this movie, I see so much of Luis Bunuel’s social satires. The Senegalese leaders all drive Mercedes and drink French bottled water, too. Sembène doesn’t deny the stylistic influence on his work, how could any African filmmaker not be influenced by the culture that kept tight control of filmmaking for decades.

Sembène also presents themes particular to his experience and his community’s experience. This is where Sembène and the characters in this story truly diverge. They have no sense of self-reflection; adopting Western capitalism is reflexive; they were living under it during the occupation and have found a way to make it benefit them. They continue the callous manner of leadership taught to them by Europeans. Yet, when Beye realizes he’s experiencing impotence, he doesn’t turn to Western medicine; he goes to the witch doctors people in his community have relied on for generations. At no point does Beye make the connection that he seeks out traditional ways in a crisis.

Beye’s desperation to prove his manhood to his new wife and the people around him results in numerous comic scenes. There’s a particular moment where Beye crawls towards his bride with a talisman between his teeth as instructed. Sembène reminds us of the same idea that Frantz Fanon tried to communicate to his countrymen – blindly returning to “tradition” as the binary counterweight to colonization is also a dead-end street. For Africa to come into its own, it must carry an honesty about its own flawed history; it cannot mythologize and canonize the past in the toxic manner that Europe does.

The final horrific sequence of Xala is Sembène reminding the audience that oppressive societies have expiration dates. Whether it’s French colonizers imposing their will or Senegalese businessmen carrying on exploitative practices, these systems will eventually create so much suffering that those who bear the brunt will violently turn against their masters. Sembène was a communist and thus holds a materialist view of the human condition. People suffer in our modern era because other people allow them to. Wealth & resources are not distributed with equity and are hoarded by those who could never use them all. By creating hierarchical societies, we encourage this behavior; the more inhumane & exploitative you are, the bigger your reward. We should not be surprised when Fanon’s Wretched come to take what they need by any means necessary.

One thought on “Movie Review – Xala”