Knife in the Water (1962, dir. Roman Polanksi)

Starring Leon Niemczyk, Jolanta Umecka, Zygmunt Malanowicz

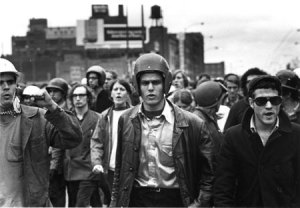

It’s funny how across the Atlantic and behind the Iron Curtain, things were much the same in both the United States and Eastern Europe in the 1960s. If you are familiar with Mad Men, then you have seen the sort of character Niemcszyk is playing. He has the slicked back hair, the suit, he’s a professional. Yet, he is also a Hemingway-esque macho man, who isn’t going to let some young upstart get away with thinking he matters. Polanksi’s first splash on the international scene is a fable-like story about some archetypal characters and relationships.

Andrezj (Niemczyk) and his wife are taking a drive through the countryside, on their way to their boat for a day of sailing. The tension is palpable in the care, neither speaks, until it is broken by a young hitchhiker standing in the middle of the road. Andrezj can tell that his wife is momentarily attracted to the young man so he offers to give him a ride, and eventually invites him onto their boat. This is all part of a disturbing psychological mind game is playing with his wife, using the hitchhiker to prove a point. As the young man flips between adolescent mood swings and is manipulated with ease by Andrezj, the older gentleman remains calm and poised, right up to the finale where both the characters and the audience are left wondering what happened and how these characters move on.

The rivalry between the two men is incredibly realistic. If you have been around immature adolescents (and sadly grown men even) you have seen the way they can get caught in a playful game of oneupmanship that devolves into a primitive fist fight. Through out the film, Andrezj intentionally puts the hitchhiker in a position of submission, giving him commands and emphasizing important maritime rules, while simultaneously breaking these same rules moments later in a bid to shove it in the young man’s face. Because of the wife’s initial flirtation with the hitchhiker we assume this is all about her, but I found that she recedes into the background till the final moments of the film. Instead, these young men are simply in a battle for alpha male status, not over a woman, but just in terms of their own relationship.

The wife is very enigmatic character, behaving without reaction for most of the film. She’s first presented as a prim and proper type, silent, not in subservience to Andrezj but in defiance of him. Once on the boat, she goes about her work mechanically, bringing about noshes when they are expected, preparing the soup when it is needed, battening down the hatches at the approach of a thunderstorm. Very subtly, her inner sexuality is revealed until she is completely nude near the end of the picture. In this moment, she defies Andrezj in a very interesting way that further pushes him down, keeping him from attaining the status of alpha.

In such a simple plot, lies an infinitely complex series of ideas and themes. In many ways, this would work as a companion piece to the similarly psychological and deceptively simplistic Funny Games. Both films are exploring weighty ideas using a framework that is easy for any audience to understand.