It began with a great white shark.

It wasn’t until the mid-70s that the concept of summer being a time to release big budget, special effects driven pictures came into the zeitgeist. Looking at the current wave of summer movies, its easy to see that science fiction and fantasy dominate, but back in the 1950s and 1960s the majority of these genre films were low budget and full of poor acting. The novel Jaws by Peter Benchley was purchased by Universal in 1973 and went through two directors before the studio settled on the relatively green Steven Spielberg. Universal’s first choice had been John Sturges (The Magnificent Seven) and then Dick Richards, who was fired after continually referring the shark as “the whale”.

To Universal, Jaws was going to be a successful film, but they never expected to be as huge a hit as it became. On June 20th, 1975 the picture was released nationwide, meaning it opened in Los Angeles and New York as well as smaller venues across the country. In the past, a film would open in a larger market and slowly spread across the country. Many film historians see this business move as the one that ensured Jaws‘ success. Up to this point the late 1960s and early 1970s had been dominated by artist driven pictures, and the studios had given up the reigns to young and headstrong young directors with a vision. Directors like Bob Rafelson (Five Easy Pieces) and Hal Ashby (Harold and Maude) had been the kind of filmmakers producing studio pictures, something very unlikely even today. In many ways, by using Spielberg, a contemporary of these young directors, but saddling him with a very studio controlled and non-character driven film, the studios were attempting to reassert their control. But the success of Jaws was nothing compared to Star Wars‘ release two years later.

There’s not much to say about Star Wars that isn’t well-known already. George Lucas, after establishing himself with American Graffiti and THX-1138, released his science fiction epic using the tropes of the serialized films of his childhood. Unlike Jaws, Lucas didn’t have a plethora of studio support behind his film and clashed with his crew, who were veterans of the film industry while Lucas was seen as an upstart. After missing its Christmas 1976 release, 20th Century Fox moved it to May 1977. Early director’s cuts were screened for Lucas’ friends, including Brian de Palma and Steven Spielberg and their reactions were disappointing. Every thing seemed to be pointing at Star Wars being a colossal failure. Lucas finally screened the picture to 20th Century Fox executives and was shocked. They loved it. One executive admitted to crying during the film at how beautiful it was, and Lucas was completely blown away from getting studio approval on a film for the first time in his career.

However, instead of becoming a studio lackey, Lucas began to build his own quiet corner of the film industry and cleverly established production facilities for sound and other technical aspects of film to create a financial safety net. Filming for The Empire Strikes Back began in 1979, with Lucas letting Lawrence Kasdan direct while Lucas supervised as producer. While the budget for Star Wars has been $11 million ($3 million over budget), Empire had a pool of $18.5 which, after a studio fire, became $22 million. Lucas always seemed to be struggling with the limitations of the contemporary technology to realize his vision. It can be seen in the concept art of Ralph McQuarrie, that Lucas wanted to make something so expansive and ground breaking. It wouldn’t be till 1999’s The Phantom Menace that he got his wish, while audiences felt the heart of the series was lost amidst masturbatory world building.

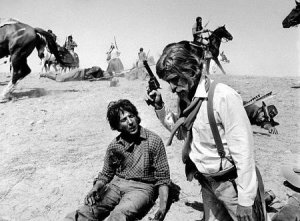

For most of the 1970s and 80s, Spielberg and Lucas dominated the summer movie. Spielberg went on to give us Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. He then teamed with Lucas to create the Indiana Jones franchise, a film series that seemed to up the ante in terms of character based blockbusters. Harrison Ford has said in interviews that he is always much more eager to play Indiana Jones again, than Han Solo. With Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Hollywood underwent a change that would shape the industry for decades to come. The level of violence in Temple challenged the MPAA’s standards and Spielberg desperately didn’t want the film to be slapped with the death sentence of an R rating. These Spielberg/Lucas films depended greatly on the viewer-ship of young audiences, particularly for the merchandising tie-ins. As a compromise, the MPAA invented the rating of PG-13.

One year after Temple, Spielberg released the Robert Zemeckis-directed Back to the Future, a film that combined special effects driven sci fi with the teen comedy. The film proved that you didn’t have to have Spielberg or Lucas directing a film to make it a huge success. Both Zemeckis and screenwriter Bob Gale were terrified that the film had not lived up to their vision and figured it would bomb. Audiences went crazy for it however, and critic Roger Ebert pointed out that at its core it shared a lot of thematic similarities with the beloved It’s A Wonderful Life. As we entered into the mid-80s, Lucas began to fade from the scene as a director and Spielberg would continue to top the grossing-lists. However, there were now a group of directors moving in to prove their own ability to pull audiences in.

Next: 1986 – 1995: Gump, Disney, and Ahnold.