The Black Dahlia (2006)

Starring Josh Harnett, Aaron Eckhart, Scarlett Johansson, Hilary Swank, Mia Kirshner, Mike Starr, Fiona Shaw, Rachel Miner

Coming off of the Euro Noir Femme Fatale, De Palma steps right into classic L.A. Noir, where the entire bleak genre really began. The film is based on the James Ellroy novel, which is in turn based on the real life murder of a young wanna be actress named Elizabeth Short, nicknamed “The Black Dahlia” by the newspapers. For the picture, we find De Palma restrained much more than in Femme Fatale. I didn’t notice too many visual flourishes, instead a lot of post-production gauziness added to the film in an attempt to make the film resemble its counterparts in the 1940s. He manages to directly reference old movies, a trademark of De Palma’s love of cinema. It’s a long picture, over two hours and there are many sub plots and third act twists. So how does it all come together?

Bleichert (Hartnett) and Blanchard (Eckhart) are L.A. beat cops who meet during the 1947 Zoot Suit Riots (sailors versus hep cats). The two men are promoted to being bond agents and fate finds them a block away from the discover of Elizabeth Short’s body. Blanchard becomes obsessed, while Bleichert becomes enamored with Blanchard’s girl (Johansson). Feeling the pressure to keep his partner from going over the edge due to the case, Bleichert does some footwork and meets a young woman, Madeline Linscott who traveled in the same lesbian circles as Short. Through a series of “what a coinky-dink” sub plots, all of these characters become entangled, ending just like all good noir should end, most every dies. The only part that really diverges is the very final scene which felt very tacked on by the studio in an attempt to not let the film end on a “sad” note. Pshaw.

This is a real mess of a film. If we were judging it on style and production design it gets an A+. That’s one thing you can never fault De Palma, the man knows how to make a film ooze style. The cinematography is pitch perfect, thinking in particular of a crane shot where as part of the background we witness the discovery of Short’s body by a mother out pushing her baby carriage. It’s done as this little thing in passing, that you could easily miss if you weren’t paying attention. That sort of clever detail is hard to not love. The entire set and costume design is solid, no one looks out of place. As always, there are some interesting set pieces that had to involve thousands of shots and takes. So from a technical stand point, its an excellent film.

Plot wise this film is trying to do way to much and tie to many things together that don’t make much sense. Characters who have no connection through the majority of the film are suddenly revealed through clunky exposition to have been sleeping with each other the entire time or connected to the murder of Short. By the time you get to the end its all so ludicrous and over the top it becomes absurd. While coincidence is a big part of noir, it at least as to make some sort of sense with the story told so far. I did however enjoy an incredibly macabre and creepy old Hollywood family that plays a crucial role in the film. While we only get a glimpse of their utter insanity, I found myself wanting to see more about them. There’s also some references to The Man Who Laughs, a Lon Chaney, Sr horror picture that served as the inspiration for The Joker. All in all, a rather middle of the road with too much plot to cram into two hours.

Next: we wrap things up with a shockingly different film, revisting Casualties of War territory, this time in Iraq, Redacted

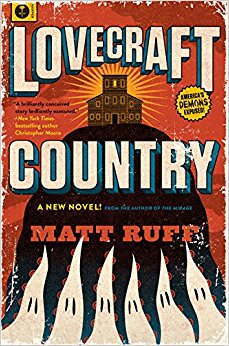

“Chicago, 1954. When his father Montrose goes missing, 22-year-old Army veteran Atticus Turner embarks on a road trip to New England to find him, accompanied by his Uncle George—publisher of The Safe Negro Travel Guide—and his childhood friend Letitia. On their journey to the manor of Mr. Braithwhite—heir to the estate that owned one of Atticus’s ancestors—they encounter both mundane terrors of white America and malevolent spirits that seem straight out of the weird tales George devours […]

“Chicago, 1954. When his father Montrose goes missing, 22-year-old Army veteran Atticus Turner embarks on a road trip to New England to find him, accompanied by his Uncle George—publisher of The Safe Negro Travel Guide—and his childhood friend Letitia. On their journey to the manor of Mr. Braithwhite—heir to the estate that owned one of Atticus’s ancestors—they encounter both mundane terrors of white America and malevolent spirits that seem straight out of the weird tales George devours […]